Following a disaster communities experience a great deal of chaos. Even with the best laid disaster response plan, organized chaos is the best you can hope for. Citizens are traumatized, in shock and searching for loved ones.

In the immediate aftermath, rescue efforts are initiated by local law enforcement, fire and rescue, and emergency medical personnel. Local hospitals initiate emergency triage protocols and adjust these as needed based on the number of injured and status of other hospitals in the area. Utility companies initiate protocols to assess the damage to power lines, water sources and gas lines. They communicate closely with local law enforcement to ensure that any unsafe areas are closed-off to the public and the area is cleared to initiate rescue efforts.

The first 24 hours involve securing the most damaged areas and making initial assessments.

The police must ensure the safety and security of local citizens, while also maintaining law and order in the community. Looting is an immediate concern for the police and for citizens. Volunteer police and all local law enforcement will flood the area to help prevent issues like this.

Search and rescue efforts are typically managed by the fire department along with local emergency response. Search and rescue starts immediately following the disaster and will continues for at least a week, or until all the missing and lost are found. Search and rescue teams will make every effort to save victims; however, after a few days the efforts will turn to strictly search efforts.

Disaster response groups like the American Red Cross, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the National Guard, the Salvation Army and many other organizations will respond to the area with resources (food, clothing, etc.) for those displaced from their homes. Some of these organizations will also offer counseling and medical services to the community.

For most communities with a current and vetted disaster response plan in place, a level of organized chaos will ensue for the next few weeks. The level of chaos will depend upon the severity of the disaster, the make-up of the plan and the amount of training conducted. Displaced families will file insurance claims and seek shelter at a hotel or with family members in the area.

Immediately following the event, a flood of volunteers and smaller disaster response organizations will be in the area, sometimes only minutes or hours following the event. An emergency response plan should ensure that someone is in charge of directing these groups and volunteers to the areas where they are needed most. A pre-established system for volunteer direction will allow for the maximum usage of this initial flood, and allows the community to establish a base of volunteers for future needs in the rebuilding process.

Among the flood of incoming groups are insurance companies. Many of these companies have large busses or some type of temporary structure that they can set up in a community response area. They are typically close to each other and near the American Red Cross location, so they can provide a hub for victims of the disaster to find services. These groups often provide food and water to the public, while providing claims services to their customers.

Once search and rescue operations have been halted, the community must look at debris removal options. If the event was declared a federal disaster by the President of the United States, FEMA funding will be available to assist with the debris removal. Local government officials will be responsible for determining what funds individuals receive from their insurance companies and how to leverage that with the funding received from FEMA for full debris removal. Typically, residents are notified when the debris removal will start and are given time to finish going through what is left of their property. While some repairs and rebuilding in areas of lesser damage may begin for those with insurance immediately following the disaster, most of the major rebuilding efforts will not begin until the debris has been removed.

Residing in every community are individuals who are without home insurance and those who are underinsured. When you add the variable of a disaster striking, some community members may fall victim to contractor fraud or the dilemma of a forced mortgage payoff. These issues will prevent the family from rebuilding and without a detailed plan in place, will cause blight.

Being prepared to create a rebuild organization prior to a disaster is optimal; however, if your community reacts immediately following the disaster, you can still greatly reduce the amount of time that will be required to fully restore the community.

For specifics regarding the local response of one community, refer to the document, Joplin Pays It Forward.

The St. Bernard Project (SBP) was launched in June 2006 in New Orleans, in response to Hurricane Katrina. St. Bernard Project’s founders, a teacher and lawyer, neither of whom had any disaster or construction experience, traveled to New Orleans six months after Katrina with the intent to volunteer for two weeks. The founders of SBP were struck by the state of recovery. Homeowners were sleeping in cars, attics and garages. Families of six or seven were crammed into FEMA trailers. Parents lost their identity as providers and children’s fundamental sense of safety and security was called into question.

Although the community lacked a clear path to recovery, the residents held a fierce desire to return home. From this the St. Bernard Project was born an all-under-one-roof disaster- recovery organization designed to ensure efficiency, prevent redundancy, and, most importantly, provide residents with a home.

After five years of successfully helping residents of New Orleans, the founders traveled to Joplin, Missouri, in order to replicate the model and assist in the rebuild there. This model was further applied to communities in New York following Hurricane Sandy and continues to provide prompt assistance to community recovery.

Since its founding in 1928 Farmers Insurance has been a company that cares about the communities where its customers, agents and employees live and work. Founder John C. Tyler believed, “The measure of our worth is not what we have done for ourselves, but what we have done for others.”

Over the years, Farmers Insurance has finely tuned its disaster response program and with this commitment at heart, in 2013, sought out a community where it could make a large and meaningful impact toward recovery. After meeting the community leaders in Joplin, Farmers invested financial and human resources, and helped author this Disaster Recovery Guide, knowing that it would be able to have a larger and more meaningful impact in communities across the country.

Rebuild Joplin was founded by community leaders almost immediately after the 2011 tornado. Initially, Rebuild Joplin sought to match people who had tornado-related needs with volunteers and donors who wanted to help.

Rebuild Joplin’s founders soon realized two compelling and related needs: The recovery needed to have a local feel, local values and a local face with the benefit of best practices and proven-effective standards and procedures. A few months after the tornado, Rebuild Joplin partnered with St. Bernard Project and a shared purpose was born, ensuring that communities recover in a prompt, efficient and predictable manner. Rebuild Joplin became St. Bernard Project’s first full affiliate.

The model creates efficiency and accountability between traditionally separate components of disaster recovery. It can also be duplicated with a proven track record in various communities across the country. The model is continuously reviewed and updated to ensure it prevents barriers to quick recovery, which are often present following an event.

The model incorporates a client management system, an enhanced construction system and a volunteer management system that saves time and money during the recovery process. This guide outlines an efficient process that will maximize the grants and donations the community receives for months, and even years, after the disaster.

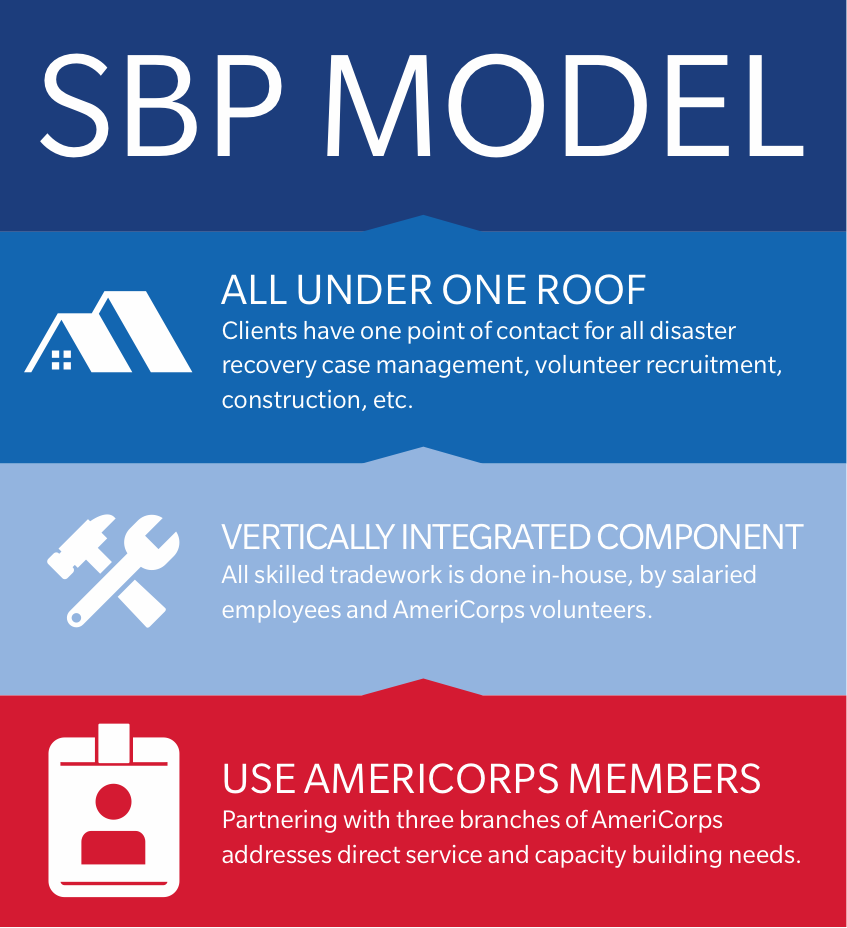

There are three components of SBP’s model.

The all-under-one-roof component of SBP’s model means that all the relevant components of disaster recovery case management, volunteer recruitment, construction, funding and scheduling are united.

The Benefits:

The vertically integrated component means that much of the skilled trade work such as, electrical, plumbing and carpentry is done in-house, by salaried employees and AmeriCorps volunteers who work under the supervision of licensed master tradesmen.

The Benefits:

SBP boldly uses AmeriCorps members to increase capacity and leverage resources. Partnering with three branches of AmeriCorps–VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America), NCCC (National Civilian Conservation Corps) and State/National Direct–addresses direct service and capacity building needs.

The Benefits:

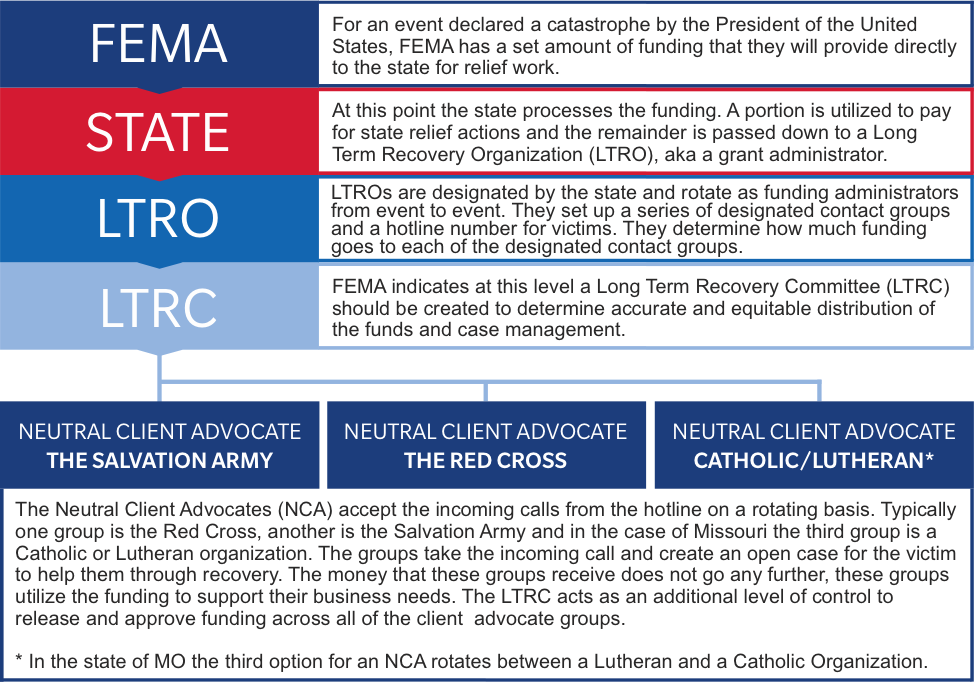

When starting a disaster recovery organization in your community, it’s important to understand the Federal Disaster Case Management system and all of its components. The process will be different for every disaster, but the information below will provide general information common for most instances. This system is intended to help a community in the first weeks and months following a disaster and will not continue throughout the duration of recovery.

The Disaster Case Management (DCM) program was developed in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, and is housed in the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Only the President has the authority to declare a feeral disaster and implement the program at the request of an impacted state with the support of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Funding for the program is granted by the Post Katrina Emergency Reform Act of 2006, which was enacted to support communities following large-scale disasters.

Disaster case managers are tasked with connecting disaster survivors to an appropriate resource based on their specific needs.

Disaster survivors are placed in the "intake" process including:

This is followed by a full needs assessment, which starts during intake and is completed or revised in subsequent meetings.

This assessment looks for:

The assessment is reviewed, a recovery plan is established and the client is provided with information and referrals to various services. If the client is in need of a home rebuild, your recovery organization may be given the referral. It’s essential you understand the disaster case management process and make connections with the various groups who will act as local case managers.

Additionally, FEMA will order that a Long-Term Recovery Group (made up of a Long-Term Recovery Organization and a Long-Term Recovery Committee) be created any time federal funding is released for a specific event.

The LTRO works as a grant administrator, using funds supplied by FEMA to the state in which you operate. For example, in Missouri, Catholic Charities or the Lutheran Organization will act as the LTRO, and administer all federally funded grants.

The LTRC works as a guardian or distributor of the funds between the LTRO and the client advocates (Catholic Charities, American Red Cross, Salvation Army, etc.). The group is made up of representatives from disaster response or recovery agencies who work directly with individuals in addressing their specific needs.

They review cases (clients) and determine where resources are needed the most. Additionally, this group would be in charge of determining the distribution of funds for any type of shared grant that is issued regarding the response. These are in addition to the grants issued by FEMA or the state.

A multitude of decisions go into the type of long-term recovery structure that will be used for your community. The system will be customized to fit the type of disaster, the impact on your community and the needs that exist.

Click here to review the source of the LTRO and LTRC information and to learn more about disaster response and long-term recovery. Additional information and references can be located on the Office of Human Services Emergency Preparedness and Response website.

Additional Resources:Administration for Children and Families (website)

FEMA Disaster Case Management (pdf)

FEMA National Disaster Recovery Framework (pdf)

FEMA Recovery Support Functions (website)

S. 3721 (109th): Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act of 2006

Following a large-scale disaster, such as Hurricane Katrina, an F5 tornado, or Superstorm Sandy, most community residents will have sufficient insurance coverage to rebuild their homes and replace their belongings. Unfortunately a large number will be uninsured or underinsured, and must rely on FEMA, family, or organizations to rebuild their homes. In other cases, homeowners may suffer from contractor fraud, forced mortgage payoffs, improper use of funds, or other disaster-related emergencies.

A rebuilding organization serves a vital role in a disaster-impacted community by providing a prompt, efficient and predictable path to recovery. It serves as a network for homeowners, community members, volunteers, donors, government agencies and businesses to collaborate and support the long-term recovery of the community. Through its impactful programs, a rebuilding organization can also add to the economic and psychological recovery of the community.

A rebuilding organization typically offers the following:

The St. Bernard Project (SBP) developed Disaster Recovery Lab (DRL) to help communities recover more quickly and efficiently. The SBP team witnessed many families in the New Orleans area struggling to recover and rebuild after Hurricane Katrina. The process was messy and the path was not clear. The result was some families gave up hope and moved away, the economy faltered for a number of years, and eight years after Hurricane Katrina, there are more than 6,000 families still trying to rebuild and return home.

DRL is a tool that disaster-impacted communities can use to help uninsured or underinsured homeowners. The methods of this guide have been tried and tested in the disaster-impacted communities of New Orleans; Joplin; and Staten Island and the Rockaways in New York. By implementing the best practices and tips outlined in this guide, communities will be in control of a faster and less frustrating recovery.

SBP believes in an all-under-one-roof model for a rebuilding organization. This structure removes all barriers to rebuilding clients’ homes and allows stakeholders to help however and wherever they can.

Your rebuilding organization should provide the following services (each item is described further in this guide):

There are several key first steps, which (if addressed) clear the way for a recovery that is efficient in the long term.

Contractor fraud is one of the biggest impediments to an efficient recovery. Click here for a link to SBP’s contractor fraud checklist. Get this checklist to as many homeowners as possible to help guard against contractor fraud.

A forced mortgage payoff occurs when mortgage holders (banks) capture a homeowner’s insurance proceeds and use those funds to pay off, or pay down, a mortgage. Forced mortgage payoffs hamper recovery because homeowners are left with damaged homes with little equity, then face challenges obtaining new mortgages or construction funds. A strong public stance by local leaders can often discourage mortgage companies from capturing insurance proceeds to pay off mortgages.

Communicate to the FEMA Voluntary Agency Liaison (VAL) the community’s desire for a prompt and efficient recovery. Open communication can result in the local, state-based and national organization working together with one goal in mind, a smooth and effective recovery.

From disaster through the first few weeks:

Below are 10 basic steps that can help your community launch a rebuilding program in three to four weeks:

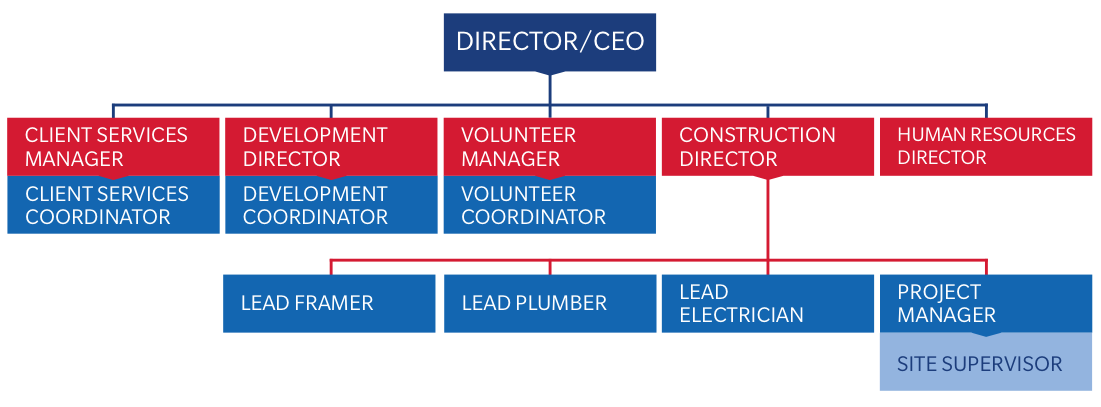

For more in-depth information on each of these positions please see their coresponding chapter.