gray 0 = [""]

gray n = ('0':) <$> gray (n - 1) <|> reverse (('1':) <$> gray (n - 1))

unwords $ gray 4

Haskell Fan Site

Software engineers are irrepressibly creative. For generations, they have devised programming languages to boldly explore new ways of expressing ideas.

But does it matter? Do the new languages help us? While I grew to appreciate certain innovations, I found I profited most from ignoring trends and following well-worn paths established by Lisp programmers decades ago. Weary and wary, I tend to dismiss the latest programming paradigm as a passing fad.

I was astonished when I found an exception: Haskell.

Try Haskell!

Haskell is so elegant and simple that I easily bootstrapped a Haskell compiler that works in the browser:

-

Ctrl + Enter: run code

-

Alt + Enter: run code then add a new cell

4-bit Gray code:

Fibonacci numbers:

fibs = 0:1:zipWith (+) fibs (tail fibs) take 20 fibs

Prime numbers:

primes = sieve [2..] sieve (p:t) = p : sieve [n | n <- t, n `mod` p /= 0] take 100 primes

Balanced parentheses:

pars = \cases

0 0 -> [""]

p q | p < 0 || p > q -> []

| otherwise -> (')':) <$> pars p (q-1) <|> ('(':) <$> pars (p-1) q

unwords $ pars 4 4

Mind Your Language

Haskell is compelling for profound reasons as well as profane ones. We focus on the latter on this page.

What do I look for in a practical programming language? First of all:

-

Programs should be easy to express.

Haskell adheres to the zeroth law. For example:

putStrLn "Hello, World!"

A complete program that can be compiled:

main = putStrLn "Hello, World!"

Pleasant syntax is a prerequisite for a friendly REPL, a basic requirement of a modern programming language. See Jack Rusher’s talk: Stop Writing Dead Programs, who also talks about "the best source code in the world".

Other languages flaunt this law, none of which I will utter here. Some languages practically confine the programmer to a heavyweight specialized IDE, and require 14 words to print 2 words.

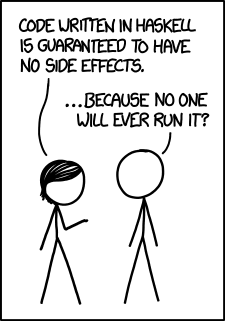

Let us now dispel a common misconception, one which I once believed:

In other words, I used to think functional programming languages were only of theoretical interest because they frowned upon side effects. Rob Pike notes that they have a "problem with I/O". Even Simon Peyton Jones himself jokingly derides earlier incarnations of the language as "useless".

But times have changed. Modern Haskell handles side effects beautifully. Our "Hello, World!" program above proves this, and we shall see many other examples.

Moreover, it has become clear that:

-

Side effects are important and therefore should be easy to express.

-

Pure functions are important and therefore should be easy to express.

-

Indicating when a function is pure is important and therefore should be easy to express.

Most programming languages respect the first two laws; the third is the tricky one. Haskell is the first widespread language to follow all three laws.

In other words, Haskell’s greatest contribution is not that it does away with side effects (such a language is indeed useless), but rather that it constitutionally separates pure and impure functions without encumbering the syntax of either.

(It could be argued this is too much of a good thing. Conal Elliott worries that side effects are too convenient in Haskell: programmers spend less effort trying to view problems with a denotative mindset. I sympathize, but I’m often consumed by the drive to get things done right now, so Haskell’s compromise suits me perfectly. See also Strachey’s opinions in the discussion at the end of Landin’s visionary paper.)

are we not pure? no sir! p…

Haskell gently forces us to distinguish between pure and impure code through its unobtrusive yet uncompromising type system. For example:

-- pal.hs

main = do

putStrLn "Enter just over half of a palindrome:"

s <- getLine

putStrLn (s ++ tail (reverse s))Without knowing Haskell, we might guess it behaves as follows when run:

$ ghc pal.hs $ ./pal Enter just over half of a palindrome: murderforaj murderforajarofredrum $ ./pal Enter just over half of a palindrome: gohangasalami. gohangasalami.imalasagnahog

The code resembles what one might write in a dynamically typed scripting language. Like such languages, Haskell has a refreshing lack of boilerplate.

However, looks are deceiving: Haskell is in fact statically typed. As we might

expect, the compiler knows that s is a string so it can prevent us from, say,

accidentally using s as a number.

More incredibly, the compiler also knows exactly which functions are impure

(putStrLn, getLine) and which are pure ((++), tail, reverse), so it

can prevent us from, say, accidentally mutating global state in a pure

list-reversing function. The compiler simply refuses to build a program which

incorrectly mixes pure and impure functions.

We’ve barely scratched the surface. See also:

-

John Hughes, Why Functional Programming Matters: Before Haskell, I thought it was a hassle to implement minimax search with alpha-beta pruning. Now, minimax only takes a few lines, which I use to build browser games.

-

Douglas McIlroy, Power Series, Power Serious. An unforgettable tour of power series as Haskell one-liners. As a tribute, I made a live demo using his code.

-

Peter Henderson, Functional Geometry. I’m a fan of M. C. Escher, and I was astonished that we can draw a simplified version of Square Limit by composing together a few well-chosen functions.

Getting Started

Install Nix. Fittingly, Nix is a purely functional package manager.

Then, to install GHC version 9.12.2:

$ nix-shell -p haskell.packages.ghc9122.ghc

Run ghci for an interactive session. Run ghc to compile Haskell programs.

To start with certain packages installed:

$ nix-shell -p "haskell.packages.ghc9122.ghcWithPackages (pkgs: [pkgs.split pkgs.rosezipper])"