On October 28th, 2007, Britain's Guardian headlined "Child sweatshop shame threatens Gap's ethical image." Investigative reporting conducted that Fall proclaimed that "despite Gap's rigorous social audit systems launched in 2004 to weed out child labor in its production processes, the system is being abused by unscrupulous subcontractors...The result is that children, in this case working in conditions close to slavery, appear to still be making some of its clothes." 1

Gap's North American President responded in a press release later that day, proclaiming the following:

"We strictly prohibit the use of child labor. This is a non-negotiable for us - and we are deeply concerned and upset by this allegation. As we've demonstrated in the past, Gap has a history of addressing challenges like this head-on, and our approach to this situation will be no exception." 2

This latest incident is but one of a litany of labor violations in retail supply chains made known in the last ten years. Gap in particular has been combating working condition violations by its suppliers for more than a decade, and since 2004 Gap has produced a Corporate Social Responsibility report detailing its improvement efforts. Factory working conditions were given 20 pages in particular in the latest report. 3

How is it that a company that has had "Sourcing Principles and Guidelines" since 1993, a company whose CEO claims it "takes great pride in operating in an ethical and socially responsible manner,"4 and a company that believes "improving working conditions in garment factories...creates tangible value" 5 has been publicly rebuked for factory condition violations in 1995, 1999, 2000, 2002, 2004, and again in 2007?

Though the instinctive summary question is "why aren't Gap's efforts working," in the following discussion we will instead ask "why do we expect Gap's efforts to work at all?" Specifically, we will articulate the logic underpinning Gap's actions, asking whether the theories in question enable us to reach desired social goals. Three such theories will be explored:

Additionally, we outline theories of change held by both activists and corporations, and present our own hypotheses about and scenarios of change.

The persistence of supply chain labor violations challenge the progress corporations like Gap assert they have made. Like all business, Gap is not rewarded for effort - it is rewarded for results. The goal of this discussion is to shed light on the theories underlying Gap's actions so we might ask whether such theories are actually helping to achieve a permanent end to supply chain labor abuse.

Theories of Value

"We are sometimes asked why we dedicate time and resources to improving working conditions in garment factories. Put simply, we believe it is not only the right thing to do, but that it also creates tangible value for Gap Inc." 6

The value of corporate social responsibility (CSR) remains in much debate, even in today's corporate context. In the above opening paragraph on the section about supply chain standards, Gap is explicitly addressing claims like those of management guru Peter Drucker, who states that "if you find an executive who wants to take on social responsibilities, fire him,"7 or like those found in the Economist, which spent almost 20 pages in 2005 surveying CSR only to conclude "the proper guardians of the public interest are governments... the proper business of business is business. No apology required." 8

Rather than confront the issue of CSR and its appropriateness in corporate America, Gap sidesteps by claiming that what it is practicing is in fact good business. This leads us to an articulation of the first proposed theory:

Indeed, in the subsequent sections of the CSR report, Gap writes, "Workers who are paid fairly, work a reasonable number of hours and operate in healthy and safe environments tend to be more productive, deliver higher-quality work, and choose to stay with factories longer than those who are mistreated." Furthermore, Gap has "heard from [its] own employees that they are proud and inspired to work for a company that is committed to improving the lives of garment workers." Given such facts, Gap is led to conclude that factory condition improvement is a "win-win" endeavor.9

According to the Economist, that makes all of Gap's factory efforts merely good management, and not rightfully categorized in the area of corporate social responsibility. Improving factory conditions would be akin to any corporate capital improvement plan or employee retention system. Yet what is notably missing from this report is any quantitative metric of productivity, cost, retention, or profit. If what Gap would have us believe is correct, it should be able to provide a graph akin to Figure 1: Optimistic net total cost vs. pay scale.

In this graph, we see total costs rising due to unhappiness and mistreatment as well as with additional pay, so from this it would make sense to pay workers at or slightly better than a living wage. The lack of any kind of quantitative justification leads us to suspect that, in fact, the pay scale more appropriately resembles Figure 2.

In this graph, real costs decline linearly as pay declines. Morale and productivity loss isn't enough to overwhelm cost reductions due to lower wages paid. Note that the purpose of this graph is not to debate the living wage per se; it is simply assumed that some kind of living wage exists and that factories choose to pay above or below that wage.

Either way, we have little concrete data on the costs of manufacturing in compliant factories versus non-compliant factories. Looking back over Gap, Inc annual reports from the 1980s through the early 1990s, we see that their cost of goods sold as a percentage of net sales went from a high of 70.9% as of the 53 weeks ending February 2, 198510, to 60-64% in the last three years11. Contrast this to Levi Strauss, who has seen cost of goods as a percentage of net sales range from 52.8% to 58.6%12 , or Abercrombie & Fitch, with 33% 13, respectively. While Gap has had a string of disappointing quarters recently, we would not expect that to be reflected in its cost of goods. A rational investor is left to conclude either that COGS was somehow lowered but Gap has a product mix unable to capture price premiums of competitors, or that the cost of "striving" to improve working conditions is not borne out in lower per-unit costs or higher customer willingness to pay.

Given the lack of quantitative data with respect to working condition improvement, coupled with the public relations benefit of releasing such data and potential fiscal obligation to release such data if it did exist, we are left to conclude the following:

Theories of Measurement

"We believe that 'what gets measured gets managed.' Monitoring provides us with firsthand insight into factory conditions and serves as an important tool to measure factory progress against our standards. Monitoring not only helps us leverage our influence with contract garment factories through face-to-face interaction, but also provides us with regular data about factory conditions and a mechanism to assess the impact of our efforts over time." 14

In recent years, monitoring has become central to the efforts at combating supply chain abuse. Gap cites 90 people worldwide who conduct more than 8500 inspections per year 15; Nike identifies monitoring as a "cornerstone" of its approach 16; and Levi Strauss believes "factory monitoring has achieved significant results on a global scale."17 Unfortunately, no industry standards yet exist on what metrics ought to be monitored, nor how one should measure this problem, or even if supply chain working conditions are a measurable problem at all. Gap has taken a lead in this area by publishing extensive measurements taken by its team of inspectors, though even with this effort, one is challenged to find discernable conclusions or takeaways.

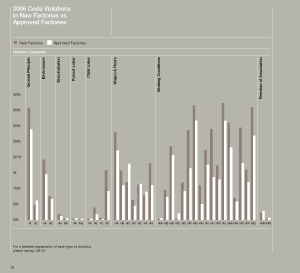

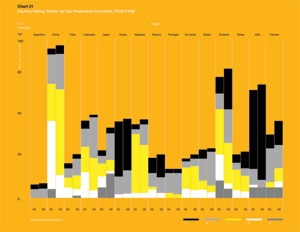

Per Gap's language, factories "progress against [our] standards." This essentially implies the existence of a continuum of compliance, and by extension, a continuum of culpability. We can see examples of this measurement model in graphs such as Figure 3: 2006 Code Violations in New vs. Approved Factories.

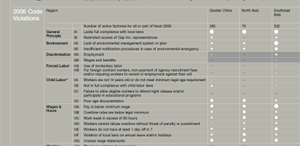

The white bars evidently represent factories already in use by Gap; the grey represent new factories in consideration for production and the codes at the bottom are classes of violations, decoded on a separate page shown in Figure 4: 2006 Code Violations Table.

In Figure 4, we see the violation classes described in further detail, along with regional indications of the severity of each problem. The size of the circle on each line indicates the severity of the problem - large circles mean that violations of a particular class were found in 25-50% of all factories, small circles mean violations were found in less than 1% of factories. Additional tables exist with information on the average time taken to respond to violations and the percentage of all factories inspectors were able to visit in the past year.

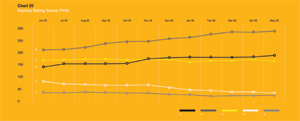

From this data, it is abundantly clear Gap is investing in measurement, that Gap has been able to pull a wealth of data so far, and that Gap is experimenting with appropriate methods of representation, visualization and analysis of such data. Contrast this with Nike, who in their most recent 2006 report established a letter-grade system that it then tracks progress against over time and in various regions, as seen in Figure 5: Nike Factory Rating Trends FY06 and Figure 6: Nike Factory Rating Trends by Top Production Countries.

Gap's closest competitor, Levi Strauss, has itself published a nearly 80-page "Terms of Engagement" document that lists standards, expectations, and suggested methods of measurement.18 Levi Strauss does not, however, publish the result of its findings or track improvement against said findings.

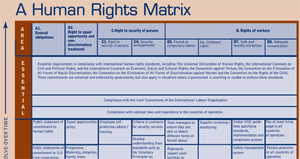

Gap goes further in its efforts to establish objectively defensible measurement criteria. The United Nations Business Leaders Initiative on Human Rights published a "Guide for Integrating Human Rights into Business Practices" in 2005. This 45-page document included a "Human Rights Matrix", excerpted in Figure 8, including essential, expected and desirable criteria in eight separate main categories. 19

As a participant company in the BIHR, Gap supplied a color-coded chart in response to this to indicate whether it provided basic, additional, or industry-leading protection of said rights in both owned and outsourced facilities, as seen in Figure 7: Human rights self-assessment.

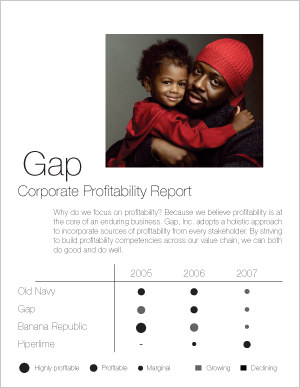

At first glance, Gap has clearly spent meaningful time both collecting data and framing it against tentatively agreed-upon standards. However, consider for a moment if the same measurement and reporting standards by which Gap has held itself were applied to its annual report as imagined in Figure 9.

While information designers may disagree, if any company attempted to convey financial data using varying circles and colors, they would be roundly criticized and mocked. What can be measured can be quantified, and to the extent such data is abstracted into shapes and colors, the diligent reader could reasonably conclude that the data was either incomplete or manipulated.

Fundamentally, there is a huge difference between managing a problem and solving it, and there are very real, ethical consequences for failing to meet compliance goals. As is detailed in the Guardian report,

"Last week, we spent four days working from dawn until about one o'clock in the morning the following day. I was so tired I felt sick,' he whispers, tears streaming down his face. 'If any of us cried we were hit with a rubber pipe. Some of the boys had oily cloths stuffed in our mouths as punishment." 20

Per Gap's methodology, this report would be classified as VA (Workers are not 14 years old or do not meet minimum legal age requirement), a violation found in less than 1% of Southeast Asian facilities, VID (Workers cannot refuse overtime without threat of penalty or punishment) found in 1-10% of Southeast Asian factories, and VIIA (Physical Punishment or Coercion), found in less than 1% of Southeast Asian Factories. In this instance, had Gap uncovered this abuse itself, "our goal is to work with factory managers to fix problems where we find them and prevent them from recurring."21

At the highest level, this approach makes sense, but when the abstraction is removed and stories are told, the theory breaks down. People do not respond to statistics - they respond to stories. Beating children with rubber hoses is not a problem, it is a crime. Alexis De Tocqueville, in his landmark American survey Democracy in America, writes:

The man who inhabits democratic countries finds near to him only beings who are almost the same; he therefore cannot consider any part whatsoever of the human species without having his thought enlarge and dilate to embrace the sum. All the truths applicable to himself appear to him to apply equally and in the same manner to each of his fellow citizens and to those like him." 22

Herein lies the difficulty of Gap's theory of measurement: Gap has a logic model in which one makes 'progress' against ethics, but the American mind sees ethics as applying equally and instantaneously across the globalized world. One might frame this theory of ethics as:

If we take a hard line, push these violations to the ends of our ethical spectrum, and reject the measures presently supplied by Gap as insufficient drivers of action or change, what and how can we measure? Certainly there is some subset of compliance issues that do exist on a continuum - working conditions and safety, for example. For the modern corporation these are quite simply capital expenditures that have known costs and locations on a balance sheet. Yet nowhere in this section do we see any indication of investments in or costs related to compliance.

In No Logo, written in 1999, author Naomi Klein states that "the fear that the flighty multinationals will once again pull their orders and migrate to more favorable conditions underlies everything that takes place."23 A Guatemalan factory owner states that big-brand clients like Wal-Mart and JC Penny are "interested in high-quality garment, fast delivery, and cheap sewing charges - and that's all."24 Garment contractors like Gap have been able to leverage their bargaining power to push down profit margins for contractors, such that, according to a 1997 UN report, "in four developing countries out of five, the share of wages in manufacturing value added today is considerably below what it was in the 1970s and early 1980s." 25

We therefore have a situation where so much pricing pressure is placed on contractors that almost all of the profit in the value chain is captured by the corporation. This leaves the contractor with no excess capital to spend on workplace improvements. Klein cites examples of factories in the Philippines that were unionized, improved, and closed when the American buyer, in this case Van Heusen, took its business elsewhere, ostensibly because of the increased cost.26

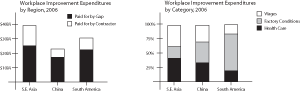

Thus, if Gap is interested in more than just quality, speed and cost, then Gap must be explicit in its measurements about what these improvements are and who is paying for the cost of such improvement. Gap should know the mean cost per garment, the expected markup and mean net income per contractor, the mean cost of condition improvements, and mean net income impact of the improvements on the contractor. From this, Gap can estimate the probability that improvements will actually be undertaken. A graph of the kind shown in Figure 10: Hypothetical Workplace Improvement Expenditures would make clear the connection between Gap's balance sheet and Gap's efforts, and show that Gap has considered both what needs to be done as well as steps that will be taken to accomplish this goal.

This leads us to our second theory of measurement:

Any company intent on measurement should be able to provide this connection. For the record, neither Gap, nor Nike, nor Levi Strauss provides any such financial data. In Nike's case, the only dollar amount described is a $100M investment in community sports organizations, unrelated to supply chain issues.27 In Levi's case, the company does detail donations of $3.01M in workers' rights grants from 1999-2005, but frames these as donations, not investments. 28

Theories of Accountability

Given the still nascent understanding of corporate social responsibly, questions of first principles remain, and none is more pressing that the question of accountability, or specifically, "why this, and why us?" Asked another way, what is the logic model of accountability for supplier-buyer relationships like those held by Gap? At one end of the spectrum, strict capitalists argue that "the business of business is business,"29 and Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman is on record suggesting that executives who prioritize social goals over profits are in some sense "immoral." 30

At the other end of the spectrum, advocates like the National Labor Relations Committee's Charles Kernaghan press for the corporation to act as a kind of proxy-activist:

"[Third-world factory owners] are harming the women in the factory. The lesson that's left behind is, if you dare raise your voice in protest, if you get involved in this human rights stuff, you're toast. The Gap is a big and powerful company. They could help this situation in two seconds." 31

In an attempt to appease both sides, Gap has essentially adopted a middle path: profits and social good are not incompatible. As it states in its CSR report,

At Gap Inc., we remain committed to delivering value to shareholders while conducting business in a way that advances the rights of garment workers around the world, lessens our impact on the environment, and provides a high quality of life for employees and those people impacted by our business. Why? Simply put: it's good business. 32

Gap has thus fused the language of advocacy with the rationale of capitalism. Yet in so doing, it has subtly shifted the question of accountability away from that of legal or ethical imperative, and toward one of non-binding moral preference. The theory that derives may be stated as:

By framing the question of social accountability as such, Gap is effectively sidestepping at least one method by which compliance could be virtually guaranteed - US and international law. Gap has already stated its intent to "follows all relevant legal standards, including international, national, and local laws," but the fundamentally weak nature of government and enforcement in the chosen countries make local laws loose at best and wishful thinking at worst.

Indeed, by Gap's own admission, 25-50% of all factories in Greater China, North Asia, and Southeast Asia lacked full compliance with local laws.33 As Kernaghan writes, "the global sweatshop economy will not be ended without enforceable human rights and worker rights standards, it cannot be done. It will never be done on the back of voluntary codes and privatization and monitoring. Never. It has to be laws."34 In other words:

Already, legal actions have gotten underway to frame supply chain accountability in terms of domestic US law. In 1999, a US lawsuit seeking more than $1B in damages was filed against Gap, Wal-Mart, J.C. Penny and others. The companies were accused of violating US federal law engaging in a "racketeering conspiracy" by using indentured labor, failing to pay overtime and creating "intolerable work and living conditions" in Saipan factories.35 The case was ultimately settled in 2002 for $20M, no admission of wrongdoing, and an agreement to put in place a monitoring program. 36

On September 13, 2005, Wal-Mart workers in collaboration with the International Labor Rights Fund sued Wal-Mart under California's Unfair Business Practices Act for similar reasons. In its objection, Wal-Mart claimed that it had no contractual obligations to the foreign workers, the foreign workers were 'incidental beneficiaries' and not directly employed by Wal-Mart, and that the claims of negligence were not, in fact, accurate.37 The suit was decided in favor of Wal-Mart, who was not held accountable for the actions of overseas suppliers. 38

Though transnational suits have so far been unsuccessful, in the realm of western law the extension of liability very clearly took hold more than a century prior. At the dawn of the industrial age in England, extensive debate took place over whether insurance-only liability for factory safety was sufficient, or whether tort liability could be extended to factory owners. As is described in Report of the Factory Commissioners in 1833 and reprinted in an article in the Oxford Journal of Legal Studies,

If...pecuniary responsibility for accidents which are incidental to the use of machines is imposed upon him (the factory owner), those consequences will be more likely to be taken into account, and to be guarded against at the time of the erection of the machinery"39

Ultimately the article describes how a hybrid model that both allowed for not only insurance but also extended tort liability took root:

Tort liability came to be perceived in the 1860s and 1870s as an instrument of general deterrence: a private law framework imposed upon the factory system capable of relieving pressures towards ever more detailed and prescriptive bureaucratization, yet without abandoning a public policy commitment to workplace safety.40

The legal debate underway today essentially replays that debate held nearly 150 years prior. While the law today hasn't been favorable toward attempts to extend the umbrella of legal accountability and tort liability across borders, the logic model behind such extensions itself remains only partially explored. Assuming that one could extend legal accountability across international boundaries, this would exponentially complicate the current business landscape. In Gap's case, more than 2,000 factories worldwide receive contracts.41 Assuming one could demonstrate that a buyer bore working-condition responsibility for the merchandise purchased, this raises the question of who and how much? Specifically, do all buyers from an exploitative factory bear responsibility? Do only those who purchase a significant share of output? Those who constitute a significant share of revenue? If Gap represents 80% of a factory's output, and small players represent the other 20%, who is accountable? What if that share is 5% Gap/95% small player? Despite all this, complexity does not necessarily abdicate one of responsibility, especially given that Gap's supply chain was of its own creation.

The key question of accountability is whether legal frameworks are necessary for change, and whether framing CSR as "good for business" slows down efforts at real change by convincing government and other stakeholders that legal protections aren't necessary. To answer this, further study is required. Ultimately, society has already decided on this question once before, and liability became law. Whether it will decide in the same way again is an open question.

Theories of Change

Irrespective of who is accountable or how the system is measured, all will agree that the global supply chain is changing dramatically, and with it factory working conditions. Yet the theories behind how such conditions change, and what it will take for socially desirable changes, remain highly divergent.

Gap's Theory of Change

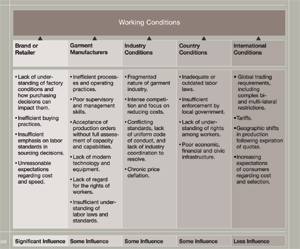

At this point in time, it is clear that Gap, Nike and other corporate leaders have been sensitive to the criticism leveled by activists and society. In providing extensive data like that in Figure 11, Gap has framed the problem of workplace conditions, but how specifically is enduring change achieved? What we find in Gap's CSR report is a holistic logic model that extends the responsibility of Gap beyond the factories under its aegis and toward garment factories industry-wide. Under the subhead of "A Holistic Approach to Improve Garment Factory Working Conditions," Gap writes:

The root causes of poor working conditions in garment factories are varied and complex. As we noted in our 2004 Social Responsibility Report, inadequate labor standards are often the result of a wide range of factors that can be difficult to isolate and address.42

Gap continues by presenting the table in Figure 11, highlighting the working conditions for its stores, manufacturers, industry, country, and world. Essentially, Gap has concluded that to solve this problem it must solve the root cause, through a combination of monitoring, contractor firing, industry consortiums and government lobbying.

This kind of thinking is a considered response to criticisms leveled by activists, such as those from activist group Global Exchange: "GAP [sic] is responsible for the entire supply chain of their garments, and for ensuring that their sub-contractors are not employing child labor or paying poverty wages - that is the price of doing business. It is time companies made real commitments to change their business model so that the root problems are corrected."43 Former CEO Paul Pressler directly echoed this sentiment in 2004, stating that "You can't look at one of these issues in isolation. They're all interwoven"44

Thus, one might summarize Gap theory of change as follows:

While reasonable in principle, this kind of expansive goal-setting comes at a cost. Holistic thinking is a virtue if it actually enables the thinker to better solve a problem; otherwise, progress can become stymied if a problem is unsolvable in a single round. By inserting the government or other industry players in between the problem and solution, Gap potentially blocks or defers progress on the factories under its own control. Gap could claim that it is waiting for other, slower players to act first or that it cannot act without improvement by those slower players. Moreover, it remains unclear that the public actually holds Gap accountable for industry conditions, country conditions, and international conditions, areas that it rightly notes it has some or little influence. The Guardian did not put Gap in the headlines because of a failure with the Indian government or garment industry in general. It wrote the article because of a failure in Gap's value chain in particular. Seeking to fix workplace standards in aggregate could certainly make society better off, but this is only true if Gap's own efforts are pursued with an unwavering urgency and immediacy.

Noticeably absent is the lack of any mention of or pressure for US legislation. Gap is working now to remove the ability of contract factories to exploit, but it could equally work to remove the incentive from itself and its peer companies to create exploitable systems by contract factories. While this might be value-destroying in the eyes of shareholders, to others the present low costs enjoyed by the garment industry are in fact part of a bubble borne out of an unfair and unsustainable situation that the market will correct.

Activist's Theory of Change

The logic model held by activists has ostensibly been one of media attention, top-line pressure through boycotts, potential and actual government intervention, and ultimate capitulation on part of the corporation. Yet history doesn't precisely bear this out. Despite media attention to its labor practices in the 1990s, Gap experienced tremendous growth, with a stock price moving from $5 to nearly $50 from 1995-2000.45 Its growth subsided only after the dot-com crash. Nike itself was identified in No Logo as a victim of global protests and proof of the efficacy of activists, yet the data point used was in the midst of the Asian financial crisis.46 Since 1998 Nike revenues have grown from $9.5 to $16.7B.47 Companies like Victoria's Secret, Proctor and Gamble, Walgreens, Wal-Mart, Microsoft, and Disney have all come under fire from boycotts and protests, yet not a single one has had even one stock analyst issue profit warnings related to such actions.

Companies are making changes, however. Why is it that a corporation like Gap alters its practices barring quantitative justification? In Gap's own words in 1995, just after the first high-profile allegations were published,

"We take great pride in operating in an ethical and socially responsible manner, and we are careful to choose business partners who share our values" 48

In a sense, the corporate ego of Gap is built atop a presumption of ethical behavior and social responsibility. In 2002, the Senior Vice President of Corporate Affairs stated:

"We have a very open mind to reach out to people, even people who might be looking to criticize us." 49

Similarly, in 2002 Gap's European spokesperson stated:

"We share the same concerns but we are proud of the work we do in factories. We're not perfect but we believe we make a difference to workers' lives." 50

Adding the quality of open-mindedness and concern for the lives of workers to Gap's corporate persona, one ends up with a company primed to act on the criticism of media, government, and activists, irrespective of proven quantitative impact. Thus, the real method of change tapped into by an activist group may well be via appeals to the social conscience of the directors of the corporation. The unspoken theory of change may be described as:

Gap changes not because of business, but because managers value and internalize the company's public reputation, one based in large part on actions consistent with statements of corporate values. While it may be the case that "the business of business is business," and the management team ought to be dismissed for destroying shareholder value on NPV-negative but socially impactful projects, to date no shareholder revolt has occurred because of CSR spending, either at Gap or any other major retailer.

A New Theory of Change

Unfortunately, neither Gap's theory of change nor that of the activists was enough to bring about improvements in time for Amitosh, the 10-year-old Indian child whose story of abuse was at the center of the Guardian article. Given the answers to the theoretical questions previously put forth, the real surprise may be the lack of even more publicized instances of abuse. Fundamentally, Gap is assuming value creation where none has been proven, is relying on measurements without standards or real cost implications, and puts forward a system of accountability that runs contrary to history and conventional wisdom of activists today. Gap's actions and activities are further obscured under the umbrella of holistic thinking. Activists have held Gap and others accountable through efforts of public shaming, but violations persist.

Given these challenges, how might the business community modify its theories to bring about real corporate improvement? We put forth the following three proposals:

As Joel Bakkan rightly describes in The Corporation, Gap as an entity is fiction, a pure legal construct. So, too, is "responsibility" at a corporate level. Amitosh was exploited because a strategist at Gap made a recommendation to a vice president at Gap who ultimately ordered an international purchasing manager to order a regional purchasing manager to sign a contract with a factory who subcontracted with the factory that employed children. At every step there was an individual, a decision-maker, who was empowered to act but legally insulated from the consequences.

Given the new era of greater transparency, lower-level employees at these corporations should expect much more public scrutiny. We may soon be entering a stage where activists identify every Gap employee who participated in a buying effort, provide links to that person's Myspace or Facebook profile, and encourage protesters to picket the homes of employees three or four levels removed from the CEO. While CEO's are paid to have thick skin, subordinates are not. We may see corporations even more sensitive to criticism in the future.

As described earlier, a real cost exists in factory improvement initiatives, and given that no corporation has conclusively demonstrated that such initiatives create value we must assume they are cost centers. Rational capitalists would respond that paying higher wages would result in noncompetitive product offerings - a mass-market sneaker company could never afford to compete in the US if they did not also manufacture in China, for example. If we grant this to be true, then the only way to remove the financial incentive for this "race toward the bottom" is to make such a race illegal. Phase in regulations such that any corporation selling products made by exploitative labor would be confiscated, taxed, or otherwise penalized. While such regulation would be complex to implement, only legal changes are enduring, consistent, and fair to all players and stakeholders in the market.

Reinforcing change only happens when the delay between cause, effect and reaction is minimal. Factories in the US don't exploit the children who are themselves US citizens because communities, media, legal professionals and government would respond within days or weeks. The comparative response delay in factories abroad is orders of magnitude. Governments are corrupt, rule of law is weak, and media can't conveniently get from the US to Southeast Asia and back.

How can we shorten this delay? It is on this point that the most tactical proposal arises. Consider the following: Cell phone penetration as of 2006 in the Philippines is at 35M users, or 40% of the total population.51 In China, 2004 statistics show that 300M people, or about 24.5% of the total population, own cell phones.52 One can reasonably claim that among third-world workers, cell-phone access, if not outright ownership, is possible today.

Further, according to Gartner, by 2009 over 70 percent of total phone sales will have an embedded camera.53 While such phones will likely be sold in first-world nations, one can also reasonably expect that camera-enabled phones will be a nontrivial percentage of phones found in the third-world within the next few years.

Video-sharing site YouTube saw 16B page views per month, ranking it among the top 50 websites in the world according to comScore in 2006.54

Finally, a quick search of Facebook lists more than 500 members who are part of the Gap network, meaning that they have @gap.com addresses and presumably work in the corporate offices (Facebook does not provide precision beyond 'more than 500' when performing searches).55

If we combine each of these market trends, imagine this scenario: factory workers who are exploited immediately bring their cell phones to videotape or provide verbal testimony to said exploitation. Those workers then send those videos, via MMS or some other Internet-based network connection on their phone, to activists in the US. Those activists translate the messages, blur the faces of workers to provide anonymity, and upload those videos to YouTube. Finally, activists purchase targeted advertising on Facebook visible only to those people who are a part of the Gap network, inviting those Gap employees to view the videos of the exploited workers. Other messages, such as online petitions, could be spread via these ads.

In this scenario, we have a highly fluid and highly targeted feedback loop such that those most empowered to fix the problem are made immediately aware. If a rush Christmas order caused incidents of exploitation to rise, employees would know it within days, not just after a monitoring group came in weeks or months later and then had findings published in a semi-annual report.

Final Thoughts

Gap is unquestionably part of a vanguard of US companies attempting to address supply chain abuse under the broad label of corporate social responsibility. Among peer companies, only Nike produces a sourcing report rivaling the detail of Gap's Social Responsibility report. Yet in spite of these efforts, supply chain abuse of the most egregious form continues to take place. Perhaps, as some might argue, Gap has received unfair criticism compared to other companies, and is certainly no worse than any other. In Gap's own words, "We really believe that we have one of the most progressive compliance programs in place...the irony is that we are one of the industry leaders."56 This theory presupposes an equality of responsibility across all companies.

To this, one might offer a different theory: Stable governments, business-friendly regulations, and a healthy and growing middle class are not rights, they are privileges. American society has chosen to reduce the burden placed on the corporation to a level that enabled business to succeed and grow at rates never before seen. In so doing society has shifted a great amount of social power away from government and into the hands of corporations. Democracy acts to limit the power of the individual, no matter how wealthy. It does not act to limit the power of the corporation in the same way. As a consequence, corporations will be judged based on how that power is wielded - and the more power, the higher the expectations.

Gap has brought the industry forward, but clearly not gone far enough, and if we accept that its actions are based on faulty assumptions, then it may well never be. Monitoring is of limited efficacy as demonstrated by the continued presence of standards violations. To have an enduring impact, Gap must show honesty about cost, transparency in measurement and expenditure, and commitment to more expansive legal accountability.

In his discussion of business at the advent of America, De Tocqueville wrote that "Americans put a sort of heroism into their manner of doing commerce," though he also astutely observed that "there is no sovereign will nor national prejudices that can struggle for long against low cost."57 If we are to recognize the latter as fact but preserve the former as truth, then the system of global commerce deployed in the world today must necessarily be overhauled, for a system premised on exploitation is one that cannot be sustained.

Endnotes

1 McDougall, Dan. "Child sweatshop shame threatens Gap's ethical image," The Observer, 28 October 2007, http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2007/oct/28/ethicalbusiness.india

2 Gap Inc. "Gap Inc. Issues Statement on Media Reports on Child Labor," Press Release, 28 October 2007, http://www.gapinc.com/public/Media/Press_Releases/med_pr_vendorlabor102807.shtml

3 Gap Inc. Gap Inc. 2005-2006 Social Responsibility Report, 2006, p. 8-37, http://www.gapinc.com/public/SocialResponsibility/sr_report.shtml

4 Fisher, Donald. "The Gap Responds to Articles on Workers," San Francisco Chronicle, 1 August 1995, http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/1995/08/01/ED58080.DTL&hw=Gap+Fisher+letter+editor&sn=002&sc=539

5 Gap Inc. Gap Inc. 2005-2006 Social Responsibility Report, 2006, p. 22, http://www.gapinc.com/public/SocialResponsibility/sr_report.shtml

7 Bakan, Joel. The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power, New York: Free Press, 2004, p. 35

8 "The Good Company," The Economist, 22 January 2005, p. 22

9 Gap Inc. Gap Inc. 2005-2006 Social Responsibility Report, 2006, p. 22, http://www.gapinc.com/public/SocialResponsibility/sr_report.shtml

10 Gap Inc. 1986 Annual Report, 31 January 1987. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis AICPA.

11 Gap Inc., 2006 Annual Report, http://media.corporate-ir.net/media_files/IROL/11/111302/reports/GPS_AR_06.pdf

12 Levi Strauss & Co. Form 10-k, 13 February 2007, p. 30, http://ir.10kwizard.com/download.php?format=PDF&ipage=4666140&source=224

13 Abercrombie & Fitch 2006 Annual Report, p. 13, http://library.corporate-ir.net/library/61/617/61701/items/246067/2006_Annual_Report.pdf

14 Gap Inc. Gap Inc. 2005-2006 Social Responsibility Report, 2006, p. 22, Retrieved 1 December 2007, http://www.gapinc.com/public/SocialResponsibility/sr_report.shtml

15 Dahle, Cheryl. "Gap's New Look," Fast Company, 1 September 2004

16 Nike Inc. Nike FY05-06 Corporate Responsibility Report, 2006, p. 17

17 Levi Strauss & Co. Citizenship - Product Sourcing Practices - Issues - Supplier Ownership, Retrieved 21 November 2007, http://www.levistrauss.com/Citizenship/ProductSourcing/Issues/SupplierOwnership.aspx

18 Levi Strauss & Co. Terms of Engagement Guidebook, Retrieved 21 November 2007, http://www.levistrauss.com/Downloads/TOEGuidebook2007.pdf

19 Business Leaders Initiative on Human Rights. A Guide for Integrating Human Rights into Business Management, Retrieved 21 November 2007, http://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/issues_doc/human_rights/guide_hr.pdf

20 McDougall, Dan. "Child sweatshop shame threatens Gap's ethical image," The Observer, 28 October 2007, http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2007/oct/28/ethicalbusiness.india

21 Gap Inc. Gap Inc. 2005-2006 Social Responsibility Report, 2006, p. 25, http://www.gapinc.com/public/SocialResponsibility/sr_report.shtml

22 De Tocqueville, Alexis. Democracy in America, Vol 1 & 2, Trans. Harvey C. Mansfield and Delba Winthrop. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2000, p. 413

23 Klein, Naomi. No Logo, New York: Picador, 2000, p. 226

25 United Nations. Trade and Development Report, 1997. Retrieved 21 November, 2007. http://www.unctad.org/en/docs/tdr1997_en.pdf

26 Klein, Naomi. No Logo, New York: Picador, 2000, p. 214

27 Nike Inc. Nike FY05-06 Corporate Responsibility Report, 2006, p. 5, Retrieved 21 November 2007, http://www.nikebiz.com/nikeresponsibility/pdfs/color/Nike_FY05_06_CR_Report_C.pdf

28 Levi Strauss & Co, Workers Rights Grantmaking, 1999-2005, Retrieved 21 November 2007, http://www.levistrauss.com/Downloads/Grants.pdf

29 "The Good Company," The Economist, 22 January 2005, p. 22

30 Bakan, Joel. The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power, New York: Free Press, 2004, p. 34

31 Ramey, Joanna. "Workers Rights Groups Slam Gap for Ending El Salvador Contract," Women's Wear Daily, 30 November 1995

32 Gap Inc. Gap Inc. 2005-2006 Social Responsibility Report, 2006, p. 8, http://www.gapinc.com/public/SocialResponsibility/sr_report.shtml

34 Bakan, Joel. The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power, New York: Free Press, 2004, p. 148

35 Wilson, Eric. "$1B in Lawsuits Filed Charging Major Firms in Saipan Labor Abuse," Women's Wear Daily, 14 January 1999.

36 Oreskovic, Alexei. "$20 Mil. Settlement In Sweatshop Suits," The Legal Intelligencer, 30 September 2002

37 Penrod, James, Brown, David and Haratani, Joan. "Wal-Mart Stores, Inc's Notice of Motion and Motion to Dismiss Plaintiff's First Amended Complaint," Retrieved on 21 November 2007, http://laborrights.org/projects/corporate/walmart/DefsMotion2Dismiss0206.pdf

38 "International Labor Rights Fund Loses Lawsuit Against Wal-Mart - 12/20/06," Workers Independent News, 19 December 2006, Retrieved 21 November 2007, http://www.laborradio.org/node/4906

39 Pontin, Ben. "Tort Law and Victorian Government Growth: The Historiographical Significance of Tort in the Shadow of Chemical Pollution and Factory Safety Regulation," Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 18, No. 4. (Winter, 1998), pp. 661-680, http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0143-6503%28199824%2918%3A4%3C661%3ATLAVGG%3E2.0.CO%3B2-K

41 Gap Inc. Gap Inc. 2005-2006 Social Responsibility Report, 2006, p. 25, http://www.gapinc.com/public/SocialResponsibility/sr_report.shtml

42 Gap Inc. Gap Inc. 2005-2006 Social Responsibility Report, 2006, p. 22, http://www.gapinc.com/public/SocialResponsibility/sr_report.shtml

43 Greenberg, Nell, "Child Labor Continues in the Apparel Industry," Press Release, Global Exchange, 29 October 2007, Retrieved on 5 November 2007, http://www.newsletterarchive.org/2007/10/29/247847-Reports+reveal,+Gap+child+labor+abuses

44 Merrick, Amy. "Gap Offers Unusual Look at Factory Conditions --- Fighting 'Sweatshop' Tag, Retailer Details Problems Among Thousands of Plants," Wall Street Journal, 12 May 2004: A1

45 "Gap, Inc Stock Report," Morningstar, Accessed 21 November 2007, http://quote.morningstar.com/Quote/Quote.aspx?ticker=GPS

46 Klein, Naomi. No Logo, New York: Picador, 2000, p. 367-379

47 "Nike Stock Report," Morningstar, Accessed 21 November 2007, http://quicktake.morningstar.com/StockNet/Income10.aspx?Country=USA&Symbol=NKE

48 Fisher, Donald. "The Gap Responds to Articles on Workers," San Francisco Chronicle, 1 August 1995, http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/1995/08/01/ED58080.DTL&hw=Gap+Fisher+letter+editor&sn=002&sc=539

49 Malone, Scott. "Anti-globalization Targets: Why Gap is Number One," Women's Wear Daily, 21 February 2002

50 Lawrence, Felicity. "Sweatshop campaigners demand Gap boycott," The Guardian, 22 November 2002

51 "Philippines telecoms: Cell phone penetration to peak at 50%," Philippine Daily Inquire, 21July 2006, Retrieved 21 November 2007, http://globaltechforum.eiu.com/index.asp?categoryid=&channelid=&doc_id=8994&layout=rich_story&search=singapore

52 Dan, Wang. "Cell Phone Usage Surges in China," CNet News.com, 7 June 2004, Retrieved 21 November 2007, http://www.news.com/Cell-phone-use-surges-in-China/2100-1039_3-5227836.html

53 "Gartner Says Worldwide Sales of Camera Phones Will Reach Nearly 300 Million in 2005," Gartner, Press Release, 1 December 2005, Retrieved 21 November 2007, http://www.gartner.com/press_releases/asset_141163_11.html

54 "Online Video Officially Goes Mainstream as YouTube.com Breaks Into the comScore Media Metrix Top 50," comScore, 15 August 2006, Retrieved 21 November 2007, http://www.comscore.com/press/release.asp?press=982

55 Facebook.com Search Results, Searching for "Gap," Retrieved 2 December 2007, https://register.facebook.com/findfriends.php?n=50431660&nm=&tab=coworkers

56 Malone, Scott. "Anti-globalization Targets: Why Gap is Number One," Women's Wear Daily, 21 February 2002

57 De Tocqueville, Alexis. Democracy in America, Vol 1 & 2, Trans. Harvey C. Mansfield and Delba Winthrop. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2000, pps. 387-390