Paths Architecture

Rough Draft March 10, 2000

emrek@cs.stanford.edu

Outline

This is a quick sketch of what I think are the main points of my paths

architecture. If you're new to paths, you may also want to read an

Overview of Paths. This document is a rough

draft. All comments are greatly appreciated. Thanks!

Path Creation and Instantiation

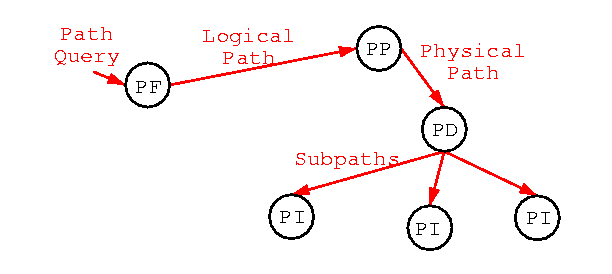

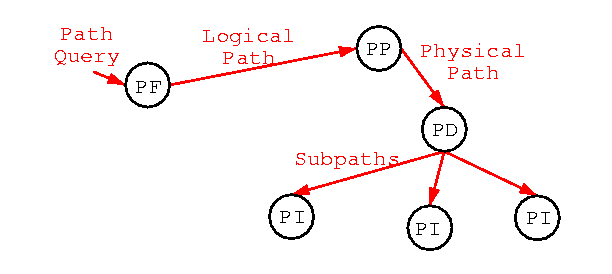

Vocabulary:

- Partial Path: an unconnected (or partially connected) path (two

adjacent operators in a path are considered unconnected if there

is a type mismatch between their inputs and outputs).

- Logical Path: A completely connected path.

- Physical Path: A logical path whose operators have been assigned

to hosts for execution.

- Path Instance: A running path. Once a path is running, information

about it (it's member operators, etc) is not explicitly maintained, and

must be discovered through introspection.

The process of creating a path is divided into three stages:

- The Path Finder: Given some request for a path, will generate a

a logical path. A request can take the form of a partial path, or a

query in a higher-level language.

- The Path Placer: Given a logical path, a path placer will assign

each operator to run on a specific host. A path placer may choose o

assign operators to run only on a single-machine, within a cluster,

or across the wide-area. Generates a physical path.

- Path Dispatcher: splits and dispatches the physical path to appropriate

hosts. Each host will receive instructions for implementing that part

of the path assigned to them.

- Path Instantiator: the path instantiator will instantiate operators

and connectors and begin data flow.

Because the path creation process is itself a path, new stages can be

added and existing stages can be replaced easily. Examples of possible

useful stages includes: adding caching operators around operators in a

logical path, parallelizing operators within a path, adding supervisor and

logging operators, and adding a higher-level query parser before (or instead

of) the Path Finder.

Figure 1: An outline of the "Path Creation" path.

Note: queues between operators are not shown in this figure

for clarity.

Figure 1: An outline of the "Path Creation" path.

Note: queues between operators are not shown in this figure

for clarity.

Path Execution

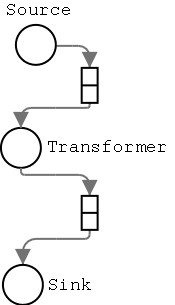

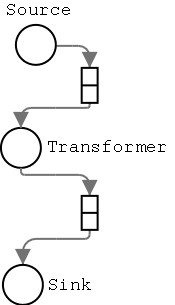

Figure 2: A simple path single-machine with source, transformer,

and sink operators. The arrows indicate the flow of data between

operators and queues.

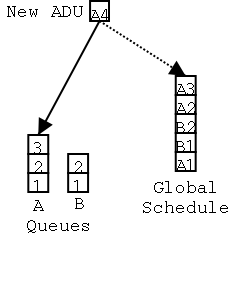

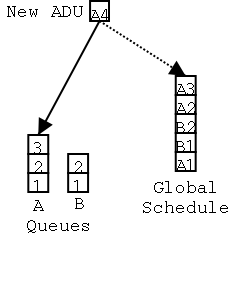

Figure 3: ADU Queues and a Global Schedule

Figure 3: ADU Queues and a Global Schedule

|

Here's a quick example of the operation of a path (see figure 1):

- The source operator generates an ADU, and enqueues it in its

output queue.

{

ADU adu = generateADU();

cfg.getQueue( "myoutput" ).enqueue( adu );

}

- When the ADU is added to the queue, the queue also adds the ADU to the

global schedule.

- The main thread in the host takes the ADU off of the global schedule. This

ADU has a reference to the queue it's in. The main thread looks up the set of

workers listening to this queue and picks one. In this example, there's only

a single worker, the transformer, listening to this queue.

- The transformer runs in the main thread's context. The operators all run

in this single thread-context. No blocking calls are allowed, though

operators are allowed to launch worker threads. There is no requirement that

an operator generate an output ADU immediately or even at all; nor do the

operator's output ADUs have to have a one-to-one relationship with input ADUs.

/* the transformer implements a receive function... */

public void receive( ADU adu ) {

ADU out = doSomething( adu );

cfg.getQueue( "myoutput" ).enqueue( out );

}

- When the transformer enqueues its output ADU, it goes through the same

process as the ADU outputted by the source operator.

- The sink operator acts just like the transformer operator, except that

it never generates any output ADUs (surprise!). A sink operator generally

displays or stores this ADU itself or communicates this ADU to some external

entity for display or storage.

|

Clusters

A basic path host is a single-node, with no networking capability built-in.

The clustering and load-balancing functionality is built on top of the path

architecture as a set of paths run by default.

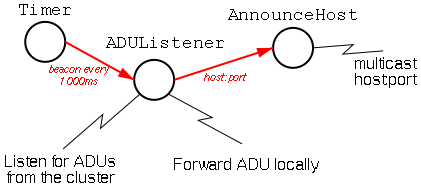

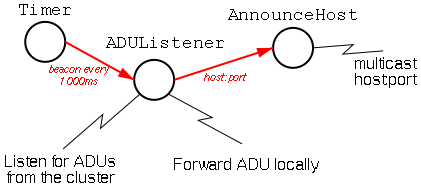

The first bit of functionality that needs to be added to make a path host

cluster aware is simple communication between machines in a cluster. What

we see in figure 4 is a path that implements a simple listener and announcer.

First, the ADUListener starts listening on some TCP port for ADUs. When

it receives an ADU, it forwards it on to a named local queue. Of course, the

existence of this ADUListener has to be known by the other machines in the

cluster. So, every second, the Timer operator sends a signal to the

ADUListener, who sends the host:port announcement to the AnnounceHost operator.

The AnnounceHost operator broadcasts this message to a well-known multicast

group/port.

Figure 4: Listening for messages from the cluster, and

broadcasting our existence.

An AnnouncementListener operator receives these multicast announcements and

forwards the list of hosts to interested operators (for example,

the cluster-placer operator discussed in the Path Creation section would

receive a list of these hosts).

This system will be extended to support a load-balancing by adding a

"load-measurer" operator, and announcing the load on a machine along with

the host:port pair.

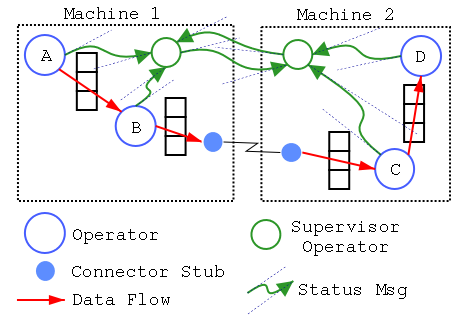

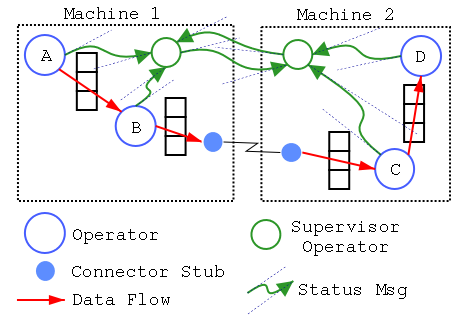

Fault-tolerance

Here's a quick proposal for adding fault-tolerance to a path. It's not meant

to be the perfect way to do fault-tolerance. Rather, it should illustrate how

this sort of functionality is easily be implemented in this architecture.

The basic idea is to have "Supervisor" operators listening to status messages

from operators. If these status messages fail to arrive or indicate some

failure has occurred, the supervisor will have enough information to restart

the failed portion of the path. Note that a Supervisor only has to know

about the operators it's directly supervising and their immediate neighbors.

To avoid clogging the network with a large number of status messages, the

supervisor can be co-located with the operators its supervising. If the whole

machine crashes, the Supervisor will need to be restarted as well. Since the

supervisor is itself an operator, it can be supervised just like any other

operator. For this case, we need to supervise from another machine.

Some fine details:

- Supervisors can be in a peered relationship with each other. Alternatively,

supervisors can be nested in a hierarchy.

- Supervisors can implement checkpointing via the beaconed status

messages.

- Status messages are not the only possible way of detecting failures.

Supervisors can also inspect the queues on the inputs/outputs of operators,

as well as listening to host announcements from the cluster.

- Supervisors can implement different policies for detecting and handling

faults for different paths, and even for different operators within the same

path. This extends further than telling supervisors to follow different

policies, completely different schemes (sans supervisors?) can be used for

different paths, even on the same host.

Figure 5: Extending a path for fault-tolerance.

Operators send status messages to their supervisor. Supervisors send status

messages to each other. If any operator fails, its supervisor will attempt

to restart it.

Figure 5: Extending a path for fault-tolerance.

Operators send status messages to their supervisor. Supervisors send status

messages to each other. If any operator fails, its supervisor will attempt

to restart it.

Figure 3: ADU Queues and a Global Schedule

Figure 3: ADU Queues and a Global Schedule