think state evidence | [colour, "raven"] <- words evidence, colour /= "black" = False | otherwise = state

Hempel’s Joke

Stop me if you’ve heard this one: 2 + 2 = 5 for sufficiently large values of 2. This is obviously a joke (though sometimes told so convincingly that the audience is unsure).

Hempel’s "Paradox" is a similar but less obvious joke that proceeds as follows. Consider the hypothesis: all ravens are black. This is logically equivalent to saying all non-black things are non-ravens. Therefore seeing a white shoe is evidence supporting the hypothesis.

The following code makes the attempted humour abundantly clear:

The state of the hypothesis is represented by a boolean. If initially true, it remains true unless we encounter a non-black raven. This is the only way to change the state. Neither "black raven" nor "white shoe" has any effect:

scanl think True [ "black raven" , "white shoe" , "red raven" , "black raven" , "white shoe" ]

Saying we have "evidence supporting the hypothesis" is saying there are truer values of true. It’s like saying there are larger values of 2.

The original joke exploits the mathematical concept "sufficiently large" which has applications, but is absurd when applied to constants.

Similarly, Hempel’s joke exploits the concept "supporting evidence", which has applications, but is absurd when applied to a lone hypothesis.

Off by one

If we want to talk about evidence supporting or undermining a hypothesis, we’ll need to advance beyond boolean logic. Conventionally we represent degrees of belief with numbers between 0 and 1. The higher the number, the stronger the belief. We call these probabilities.

Next, we propose some mutually exclusive hypotheses and assign probabilities between 0 and 1 to each one. The sum of the probabilities must be 1.

If we take a single proposition by itself, such as "all ravens are black", then we’re forced to give it a probability of 1. We’re reduced to the situation above, where the only interesting thing that can happen is that we see a non-black raven and we realize we must restart with a different hypothesis.

We need at least two propositions with nonzero probabilties for the phrase "supporting evidence" to make sense. For example, we might have two propositions A and B, with probabilities of 0.2 and 0.8 respectively. If we find evidence supporting A, then its probability increases and the probability of B decreases accordingly, for their sum must always be 1. Naturally, as before, we may encounter evidence that implies all our propositions are wrong, in which case we must restart with a fresh set of hypotheses.

For example, we may take A: "all ravens are black", and B: "there exists a non-black raven", and assign each a nonzero probability. Now it makes sense to ask if a white shoe is supporting evidence. Does it support A at B’s expense? Or B at A’s expense? Or neither?

I would say neither, given the wording, though we can make the propositions more specific to change the answer. What if we’re talking about a video game with simulated ravens which change colour if they land on a white shoe, due to some bug? Or the same game after they patch the bug so ravens always stay the same colour? See Chapter 5 of Jaynes.

A Card Trick

Instead of trying to flesh out hypotheses involving ravens, let us content ourselves with a simpler scenario. Suppose a manufacturer of playing cards has a faulty process that sometimes uses black ink instead of red ink to print the entire suit of hearts. We estimate one in ten packs of cards have black hearts instead of red hearts and is otherwise normal, while the other nine decks are perfectly fine.

We’re given a pack of cards from this manufacturer. Thus we believe the hypothesis A: "all hearts are red" with probability 0.9, and B: "there exists a non-red heart" with probability 0.1. We draw a card. It’s the four of clubs. What does this do to our beliefs?

Nothing. Neither hypothesis is affected by this irrelevant evidence. I believe this is at least intuitively clear to most people, and furthermore, had Hempel spoke of two hypotheses and hearts and clubs instead of ravens and shoes, his joke would have been more obvious.

A winner is you!

Hempel’s joke reminds us we must consider more than one hypothesis if we want to talk about supporting evidence. Assigning degrees of belief to a lone proposition is like awarding points in a competition with only one contestant.

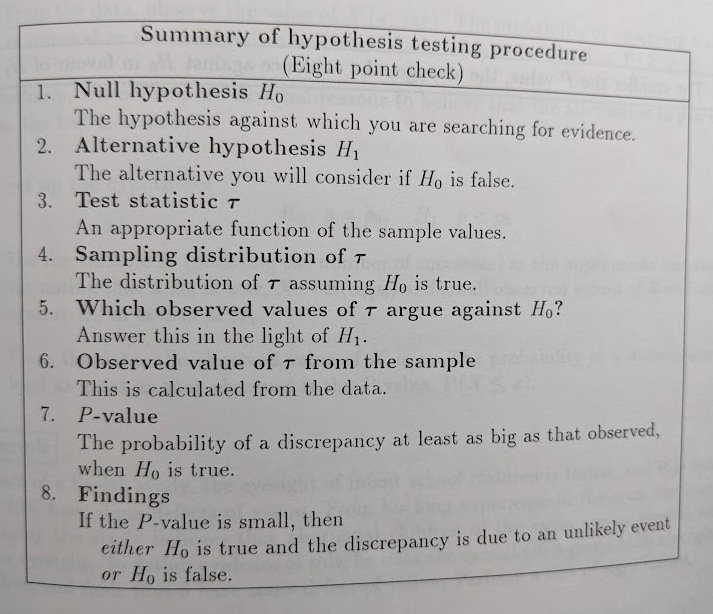

This all seems obvious, but apparently it is not obvious enough. Not only is Hempel mistaken, but my own introductory probability and statistics textbook also instructs us to consider only one hypothesis. Actually, it’s worse: it instructs us to devise an alternate hypothesis, which sounds promising, but it turns out to be strictly ornamental. (Step 5 is to answer "in the light of" the alternative hypothesis, that is, write anything about it so long as you avoid Bayesian reasoning!)

So what should we be doing? See Chapter 28 of David Mackay, Information Theory. Briefly:

-

Invent models (hypotheses) and gather data.

-

Fit any parameters in the models to the data (via Bayesian reasoning).

-

Assign preferences to the models using the data (via Bayesian reasoning).

-

Decide what to do next. For example, if all the models seem to be a poor fit for the data, or if their predictions are of little use, then consider going back to step 1 to invent new models or gather more data.

Steps 2 and 3 are where we take into account evidence such as black ravens or white shoes. Sometimes the evidence changes parameters in step 2. Sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes it affects our preferences in step 3. Sometimes it doesn’t. It all depends on our hypotheses.

We walk through a simple example. Suppose we find a coin. We invent a single model that says the coin shows heads or tails with equal probability. We gather data, flipping the coin 20 times. We observe 20 heads in a row. Steps 2 and 3 are trivial because we have a single model with no parameters, and by default, it is our preferred model (Hempel’s joke).

Next comes step 4. What should we do next? Are we satisfied with our model? Maybe it’s good enough for our purposes; maybe not. Perhaps we think we can explain the data better with a second model, one that says the coin has heads on both sides.

As we have two models, we assign them prior probabiltiies. We profess maximum ignorance, so by the principle of indifference, either model has even odds of being correct.

Step 2 is again trivial since none of our models have parameters to adjust but this time, in step 3, we can compare the models with the data we gathered. Let \(H_0\) be the hypothesis that the coin is balanced, and \(H_1\) be the hypothesis that it has heads on both sides, and \(D\) be the data, namely, twenty consecutive heads. Bayes' rule states:

\[ P(H_1|D) = P(D|H_1) P(H_1) / P(D) \]

This is:

let pdh = 1 ph = 1/2 pd = (1/2)*(1/2)^20 + (1/2)*1 in pdh * ph / pd

The new model is now much more probable.