A Thoroughbred in Harness

A Thoroughbred in Harness

On the trailer, Proton lay with her muzzle between her paws. I thought I noticed her stir when we turned onto Route 128 towards the Mass. pike instead of Interstate 93 towards the launch ramp in Weymouth. But maybe I imagined it. She was quiet as the van and trailer rolled west towards upstate New York. As we crossed the bridge over the wide Hudson in New York, Proton pricked up her ears and lifted her nose to smell the water, but as the river fell behind us, she sighed and put her muzzle back between her paws. She seemed resigned, even depressed, as we descended the steepish hills towards Ithaca.

We launched at the Allan Treman State Marina on Cayuga Lake in Ithaca. As Proton spread her amas in the fresh water, she seemed to me curious, testing this unfamiliar medium. Could she tell that it didn't buoy her up as much as the salt sea she was used to? Certainly the water smelled different.

Cornell University loomed "high above Cayuga's waters" as Skipper Ken, Judy and I loaded our gear onto Proton and motored out past the breakwater. Proton shivered in anticipation as we hauled up the mainsail and unfurled the jib. The wind blew straight down the lake, increasing from ten to twenty knots, and we started the first of many tacks between the cliffs of Ithaca shale. Proton was in her element. She tossed her head and seemed to snort with eagerness as we beat back and forth in one foot waves. (Can we call them "seas" in fresh water, we wondered?) As the wind increased we reefed the main. It was Wednesday, the second week of July and we had the lake to ourselves.

We spent the night at Cayuga Lake State Park at the north end of the lake. In the morning, we folded the boat and took down the mast, demonstrating for a family considering purchase of an F-boat. Then we set off up the Cayuga-Seneca Canal, along the Montezuma Marsh, our 8-horse outboard pushing Proton along sedately at five knots. Soon we came to our first lock, CS-1. None of us, including Proton, had ever gone through a lock before. Festooned with fenders on both sides, we putted into the lock and looped our mooring lines behind the inset pipes on the walls of the lock. Ken bought us a two-day permit for the New York State Canal System. There was only one other boat, a cabin cruiser, in the lock, and we sank uneventfully as the lockkeeper let out the water. The descent was only 8.9 feet, but we pointed Proton's nose out the gate on the downstream end with a feeling of accomplishment. We were on our way to Lake Ontario!

The speed limit in the canal is 10, so we were well within it as we motored along. In just over an hour we were at the junction with the Erie Canal. Ken dug out our battered copy of Rise Up Singing (it goes with us on most cruises) and we sang several verses of "Erie Canal":

Oh, I had a mule and her name was Sal. Fifteen miles on the Erie Canal.

The whole day we saw only six other boats using the canal. The air was brisk, windy and clear, and the sun shone brightly. Everywhere we looked there were great blue herons, osprey, buzzards, Canada geese, mallards, and kingfishers. Purple loosestrife, a beautiful invader, adorned the banks. We were puzzled because there was no tow-path. Where did Sal the mule walk when she towed canalboats along? Later we learned that the original hand-dug canal with towpath was abandoned in many places and rerouted into dredged rivers, once motorized vessels obviated the need for muscle-powered towing. Sometimes abandoned canal sections were visible next to the river.

We tied up for the night along the wall in Baldwinsville, just upstream of Lock 24. There were a number of other boats, none of them sailboats, also tied up. We had a few minutes of dread when we noticed a band-shell with chairs set up across the river and feared we might be kept awake till the wee hours by loud music. However the concert wasn't till two days later. And even the next boat's roaring generator was courteously turned off at a decent hour.

We went ashore and walked down to the Lock 24 Restaurant and had dinner. There were no showers, so we resigned ourselves to wearing our sunscreen, grime and sweat for another 24 hours. The next morning, I got up early and walked into town for coffee. On the way back, I watched a sailboat with its mast down enter the lock from the downstream side. I hailed them. "Did you come from Lake Ontario?" "Yep." "How was it?" The response was a gesture suggesting large waves. I trudged back to Proton. The others were up. We had breakfast and were the first down-stream traffic in Lock 24. The lock-keeper looked at our permit and waved cheerfully. This was an 11-foot drop and again proceeded without incident. Judy and I sat on the ama and held onto the lines. I had a ladder this time, instead of a rope, so I had to keep changing the line to a lower rung as we went down, but it was not difficult. The tendency of the up-stream gates to leak water in a roaring fountain was a little scary, but we soon learned that all the lock gates leaked.

We negotiated eight locks that day, and motored some thirty miles-two mules named Sal. We crossed the end of Cross Lake, banging through waves, which seemed remarkably big after two days of smooth canals. We saw cormorants which seemed different from the ones we were used to seeing in Cape Cod Bay-browner, and more likely to fly in lines and v's. We also saw a green heron. I did a double-take at the unmistakable silhouette of a pelican . . . has global warming progressed that far? Pelicans in New York? But it was a bronze statue.

We saw very few other motoring boats that day. We had planned the canal part of the trip for midweek, to avoid traffic, and we were surprised at how effective this tactic was! Surely the lock system cannot be supported by user fees, given the dearth of traffic. Every lock seemed to have two employees-one operating the machinery and checking passes, and one engaged in painting or other maintenance. Everybody we encountered in the lock system was courteous and helpful and we seldom had to wait very long for a lock to be opened to us. The biggest drop we had was 27 feet, at Fulton. The wind whirled around in the cavernous space left behind as the water drained away. Most times the keeper of one lock would call ahead to the next lock to let them know we were coming, and so the locks were often ready to receive us. The only time this system broke down was at a shift change.

There were many moored boats and boathouses along the rivers. Most boats were on risers of some kind. Many lawns had heron statues on them, and so we had to look twice to see if a heron was alive-not an easy distinction, because a fishing heron is a very still and patient bird. I was struck, not for the first time, by how seldom we saw a heron actually catching something.

By late afternoon we had arrived at Oswego International Marina. Proton's stint as a canal boat was over. I likened using an F-27 for canal cruising to harnessing a thoroughbred horse to a plow. But Proton didn't seem to mind.

A nuclear power plant loomed over the entrance to Lake Ontario, and twin smokestacks from some other installation guarded the other side. We watched waves break over the breakwater with some trepidation. The sailboat in the lock had told us true. We tied Proton up along a wall, and raised the mast. We slanted the boat at the wall where we had moored, just enough that Ken, standing on shore, could reach to re-install the antennas and Windex. Ken was concerned about the Windex, but managed to wedge it in place with the judicious application of a little duct tape. We hoped it would hold. (It did.) Then we dived gratefully into the showers, did laundry and walked into Oswego for supper. This time we did have an outdoor concert, at the bar at the marina-but it was not very loud, stopped at nine o'clock, and besides was a performance by an acoustic guitarist who sang songs we knew. We enjoyed singing along as we put the boat to bed.

In the morning, after a rather bumpy night, we chugged across the harbor to get gas and pump-out and water so that we would be in good shape to start out across the broad lake. I savored a cup of free coffee. One of the bowlines in the mooring lines came untied and Proton's bow drifted away from the gas dock. We retrieved her with no harm done. Proton nosed out past the breakwater and we were out in the lake, headed for the Thousand Islands. "We'll sample lots of salad dressing!" I said. "There's probably no more salad dressing in the Thousand Islands than French toast in France," Ken predicted.

The 15-knot wind was in our teeth. Judy and Ken put on their foul weather gear. Oops! We noticed we had never rigged the jackline. I crawled out on the bow to slip the blue webbing under the bow cleat, holding on tight as the plunging deck made me alternately weightless and heavy. A big wave broke over the bow and soaked my tee-shirt and jeans. But it was fresh water so I didn't mind very much and presently I was dry again. One of the things we'd been looking forward to about this trip was the fact that when things got wet they could get dry again. Salt water trips are much more sodden, since when fabric gets wet with salt water it tends to stay wet until washed. Ken hove to long enough for Judy to re-knot the jib sheets with smaller bowlines so we could sail as close to the wind as possible. It was a wet, exciting ride and Proton seemed to exult in doing the work she was made for. We watched the twin smokestacks and the nuclear power plant recede over the horizon. "It's hull down," I said, "or it would be if power plants had hulls." I've read entirely too many Hornblower books.

I took the chart kit below to find us a waypoint to enter on the Loran. Our goal was a New York State Park on Point Peninsula. I entered a waypoint in the reach between Stony Island and Galloo Island. The motion of the boat made focusing on the tiny numbers on the chart rather difficult, and I was glad to get back on deck in the wind and fresh air before even my cast-iron stomach rebelled. Ken took an extra Bonine, and even Judy, who like me is usually immune from seasickness, took one. We began to see islands ahead. "It could be Casco Bay, Maine," I said, "except the trees are the wrong shape. They're all deciduous, and Maine is the 'country of the pointed firs'."

As we got in amongst the islands, the wind moderated and came around behind, and we cruised along Point Peninsula watching the cars and camps and bicyclists go by. Long Point State Park is on a narrow inlet on the north end of Point Peninsula, which is as nearly an island as a peninsula can be. Our guidebook had said Long Point took dockage reservations and we didn't have one, and it was Saturday night. So we tried to anchor in the inlet, but neither the Bruce or the Fortress would hold in the weedy, soft mud bottom. We weighed the anchor and motored to hail one of the sailboats at the dock. "What's the procedure?" He told us to tie up in any slip without a "rented" sign and walk down to the ranger's house to pay up. We tied up and Ken and Judy walked through the campground over to the ranger's while I went about the chores of putting the boat to bed. I moved the halyards from the mast to the pulpit, slackened the shroud tighteners, secured the tiller and daggerboard, and piled the mainsheet on top of the solar- powered fan in the roof of the aft cabin so it wouldn't come on in the early morning sun and wake Judy up. One of the campers told us that there weren't any mosquitos and she was right. We would later remember this gift with gratitude. We made dinner, took showers and spent a quiet night.

The next morning we beat down past Point Peninsula at five knots, leaving a monohull behind. Rounding the south end, we flew the spinnaker into the St. Lawrence River. We had intended to spend that first night on the river in a municipal marina in Clayton, NY, but when we got there the water was rough from wakes and the floating dock was clanging violently as it heaved up and down. We tied up long enough to walk into town and buy groceries and ice, and then we sailed downriver to Canoe State Park. It seemed strange that we were going downriver-when you enter a river from a large body of water it feels like going upstream.

Canoe Point State Park is on Grindstone Island, one of the large islands which divides the Ontario end of the St. Lawrence into several large channels. The park is accessible only by boat and has limited facilities. Again, we were lucky enough to get dock space. Canoe Point was beautiful. In the night, Mars blazed orange in the south next to fainter orange Antares. The Milky Way arched across the midnight sky. We spent a good part of the next morning hiking on lovely trails overlooking the water. We saw a loon and heard its haunting call. Blueberries and red and black raspberries were ripe and we grazed as we went. After our land-based amusements we motored through a narrow channel called, appropriately enough, "The Narrows", and headed for Boldt Castle.

George Boldt, a wealthy New York City hotelier, built a fairy tale castle for his wife on Heart Island. It is now operated by the Thousand Islands Bridge Authority as a tourist attraction. Like most millionaires who vacationed in the Thousand Islands at the turn of the century, George had yachts. We learned that George had directed the chef on his yacht to develop a new dish to be named in honor of the islands. The result, served in the Waldorf Astoria, was Thousand Islands dressing. "See!" I shouted triumphantly at my previously skeptical crewmates, "I told you so!"

Leaving Boldt Castle, we motored for lack of wind to Kring Point State Park, which is on the New York mainland and caters to RVs and campers. There was no room at the dock, so we tried several times to anchor. Ken even reconfigured the Fortress in its "soft mud" version, but we couldn't get it to hold. Why does one always have interested spectators while failing to set an anchor? While we were hanging gingerly on the un-set Bruce, disgustedly wondering what to do next, we noticed that a space had opened up at the dock. We hurriedly dragged up the weedy, muddy anchor and grabbed the space. Ken went ashore to pay the dockage fee, and discovered that, unlike the other NY state parks we'd visited, this one didn't expect that people might sleep on their boat at the dock. The ranger scratched his head and decided to charge us the fee for an "extra car"-$6.00. We swam at the swimming beach, squealing as we swam through chilly thermoclines, showered, made supper, and went to bed. The mosquitos were wicked. In the morning, we looked at the park brochure. It told us that nearby Ironside Island, owned by the Nature Conservancy, was the largest heron rookery in the area. We decided to sail by it on our way.

We were glad we did. Less than half a mile long, the island hosts hundreds of heron nests, most easily visible in dead trees which held five or six four-foot nests each. We saw many herons, but it was too late in the season for young ones. After sailing downwind and downriver along Ironside Island, we crossed the international border just downstream of Grenadier Island and beat back upwind and upriver in a wide passage with a deep shipping channel in the middle. We were navigating like mad, making sure to tack before the shoals. The passage narrows to run between Tar and Grenadier Islands and then under the Thousand Islands Bridge. Once we had to luff up to avoid being run down by a tour boat, and once we had to start the motor because the current was setting us back under the bridge. We were tired when we dropped the sails outside the Gannanoque Municipal Marina.

Gannanoque was our first Canadian stop. We cleared customs and immigration by a simple phone call to a toll free number from a pay phone on the dock. This marina was delightful. The facilities were modern, clean and ample. I left four or five paperbacks I was through with in the ladies room with a note for folks to help themselves, and the next time I visited they had disappeared.

Along one side of the marina was a row of dilapidated boathouses. A squealing, crunching noise attracted our attention and we looked just in time to see one of them collapse under the ministrations of wreckers. Suddenly it was clear why another boathouse farther along had "good bye cruel world" painted on its side in large black letters. We got another giggle over the neatly lettered sign on the dock, "You must clean up after your dog. Any deposits left by your dog will be delivered to your boat free of charge." I saw a dog on the dock and engaged in my usual speculation about the breed-I thought it resembled a Springer spaniel, but it was black and white and more heavily feathered than I thought a Springer would be. The owner assured me the dog was in fact a Springer-they do come in black-and-white although liver-and-white is more common. We showered and did laundry and walked into town.

Gannanoque is the site of a battle in the war of 1812 when American rebel forces defeated loyalist defenders. The town didn't seem to hold the loss against its US visitors. We had a gourmet meal at the Gannanoque Inn, marred only by the fact that, as Ken said, the foundations needed work. In fact all that was wrong was that we all had "sea legs", so that solid ground seemed to be rocking like a boat. We walked along the waterfront and looked at tee shirts.

The next morning I went in search of coffee. While drinking it on a bench on the waterfront I saw a man walking a liver-and-white dog which I would otherwise have said was a border collie. It was in fact a border collie, the man said. Black-and-white is more common but there are liver-and-white ones too. I shook my head at the strange Canadian dogs.

After the others were up we walked to the A&P in town and bought groceries, including some local sweet corn and some Thousand Island dressing. We pumped out and bought ice and topped off the water tanks. We found pump-out easy to obtain on this trip. All of the waters we sailed were in a no-discharge zone, and we had had to disconnect and seal off the overboard discharge pipe from the head in order to be legal. No one ever checked, but we wanted to be responsible boaters.

Our next destination was Camelot Island, a provincial park where a friend of Judy's had stayed. The friend had waxed so ecstatic about the island that we made a point of going there. It wasn't very far away from Gannanoque, so we spent some time sailing randomly on fast reaches around the wider part of the channel, recovering from all the narrows we'd coped with the day before and satisfying Judy's desire for some fast sailing.

On the way to Camelot Island we passed islands with strange names: Dumbfounder, Bloodletter, Belabourer, Deathdealer. Camelot seemed peaceful by contrast, and it was certainly lovely from the water. We found a protected cove where a number of monohulls were anchored and we tried to emulate them, but, again, had difficulty anchoring in the soft mud and weeds. We finally got a set but the anchorage was very crowded and we worried that a change in wind might swing us into the other boats. We have had trouble before, because multihulls and monohulls don't hang the same way.

For the first time, we got out the dinghy and rowed ashore. From the dinghy dock we walked along a trail and found ourselves at a set of docks we'd seen from the water. From this vantage we could see that there was in fact a space big enough for us at the dock. I grabbed my book and sat on the dock next to the space, ready to repel boarders, and Judy and Ken went back for the boat. The other boats were cabin cruisers and houseboats. We saw a lot of these latter boats. Like campers on pontoons, they are for rent in the Thousand Islands. Our neighbors were very pleasant and apologized nicely for running their gen-set for an hour to cool down their refrigerator. There were picnic tables and tent sites, but most people seemed to be staying on their boats. There were decent outhouses, too. And mosquitos. LOTS of mosquitos. HUNGRY mosquitos.

While we were cooking our corn, an itinerant marine (riparian? littoral?) pedlar motored up to the dock. He had soft drinks on ice and staples. We bought butter for our corn from him. We drank his soft drinks while we looked at the chart and decided how many more nights we wanted to do this.

In the morning we hiked around the island listening to birdsong and eating berries. I gave away another paperback. At the information kiosk we solved a mystery. The islands with the bloodthirsty names we'd seen the day before, along with Camelot, were named after a fleet of British gunboats. The little archipelago is called "The Lake Fleet."

From Camelot Island, we set off flying the spinnaker in burning sun to Loyalist Cove in Bath, Ontario. The marina there was a bit dilapidated but had all necessary facilities. The young man who stood by to catch our mooring lines was really impressed with our trimaran. "Gee! Just like 'Water world'!" he said, and raved about how really cool our boat is. We agreed with him of course. It occurred to us then to be puzzled that no one had said to us, "We had a buncha them funny lookin' boats in here last week." We knew Bob Gleason had organized an F-boat cruise in the area the week before, but we never met anyone who said they had seen them.

After making the boat secure, we walked down to the Last Chance Café-it was not clear whether it was the proprietor's last chance to make it in business, or the last chance to eat for a while. An informational sign in a park told us that this part of Canada became home for loyalists who left the Colonies after the success of the revolution.

When we returned to the marina, we were entertained for a long time by a lively golden retriever. Someone on the dock would throw a stick and the dog would leap into the water five feet below with an enormous splash. This went on until the thrower's arm was tired. The dog wasn't. Shortly, a woman came by headed for a monohull tied up beyond us, and warned us that the local mosquitos would be out in force in four minutes. We scurried around velcro-ing up the mosquito netting and the kamikaze attack started right on schedule. To avoid them, Judy made her trek from the main cabin to the aft cabin via the sub-cockpit, "slithering" route.

In the morning, the proprietress stopped by to collect our money. "A dollar a foot," she said, and I said, "We're twenty seven feet long." "It'll be three times that," she said, deadpan. But of course she was kidding.

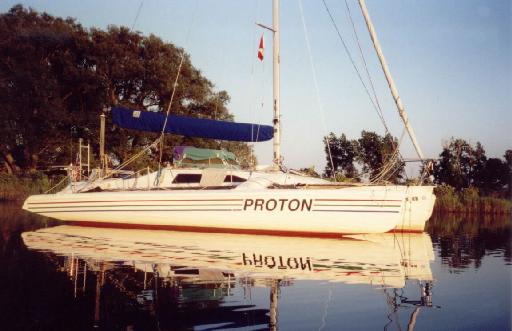

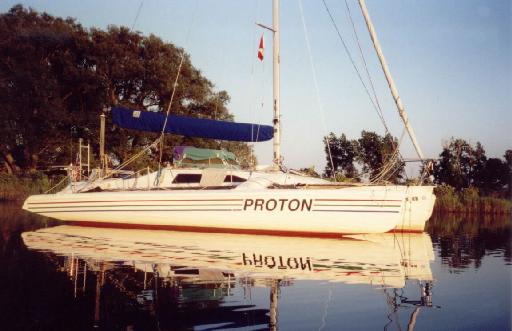

We set off for our next-to-last stop: Main Duck Island, about halfway across the eastern end of Lake Ontario. Close-hauled in light winds, we got there early in the day. The island is the larger one of the two "Duck Islands"-the other one is called Yorkshire Island, for no apparent reason. Main Duck Island is a provincial nature preserve and has virtually no facilities. The marsh- covered island is almost bisected by a narrow cove, which reminded us of Cocktail Cove on Jewel Island in Casco Bay. Taking advantage of our shallow draft, we left the rudder halfway up and floated the daggerboard to creep past several monohulls and cabin cruisers to the very head of the inlet. After some difficulty we got the Bruce to hold and then went ashore in the dinghy to look around. We found a primitive toilet which would have been welcome except for the guardian poison ivy which hung over the narrow path. We did not walk as much on the island as we might otherwise have done! We went back to the boat and swam for a while, sharing the water with a turtle. In the evening, Proton's reflection in the calm water was very clear (pictured above). That night Mars and the Milky Way were spectacular.

When we woke up there was wind! We thought we would be at Sandy Pond on the east end of Lake Ontario by early in the day. The wind was unfortunately blowing 17 knots from the direction we wanted to go, but nevertheless we made good progress for a while, feeling good about the coming end of the trip. "Clipper ships," Ken mused, "were said to be 'the greyhounds of the sea', but actually I think trimarans are more like greyhounds than clipper ships are. After all, trimarans like this one are made to go fast, but they can't carry anything much. Clipper ships carried cargo." It was an interesting and perceptive reflection, but I was mainly gratified because I had long thought Proton had something of a racing animal about her. My fancies have never clearly differentiated between a dog and a horse, though, as readers of the first part of this article can attest.

The wind stayed strong long enough for us to show up a monohull which left the cove at about the same time as we did, but it dropped around midday and we motored the last few miles to the opening into Sandy Pond. We were headed for North Sandy Pond Marina, which the guidebook had told us had showers and transient slips and a good ramp and was adjacent to a pump-out station.

We were astonished at the line-up of power boats beached on the sand under the dunes marking the entrance to the inlet. Once inside the pond, there was a little wind again and we sailed the length of the shallow pond, only motoring the last bit towards the marina. We tied up at the gas dock and Ken consulted with the proprietor. He sent us off with vague directions to the pump-out station and we tried to follow them. We had only a little gas left in the tank and we didn't want to refill it from the reserve tank since we wanted the boat to be as light as possible when we put it on the trailer. The reserve tank we could empty into the towing vehicle. So, we were nervous about running out of gas, constantly on edge because the depth alarm kept going off, needing to stop every little while to disentangle weeds from around the propeller. We tied up to a nearby marina with pump-out and Ken went to find the attendant. There was only one person on duty; she couldn't leave the restaurant. There wouldn't be anyone else there for another hour.

We decided not to wait, and this was a decision we would come to regret. We went looking for the next pumpout. We hailed an elderly man who had waded into the water up to his neck fully clothed and wearing a hat. He hailed back, "You're talking to a guy without his hearing aids. I can't hear you." We tried again, with a man in a boat this time, and he directed us to the next pumpout. We'd passed it already. It was nearly invisible, accessible only after negotiating a winding, minimally bouyed channel. And when we got there the dock was only about six feet long and the pump-out truck had to be fetched, and then the hose was too short to reach and Ken had to turn Proton around in the tiny basin. Everywhere, people were working on their outboards, and the noise and the heat were fierce. And then it was MY turn for a mooring-line knot to fail and I had to make a wild grab for the dock as Proton started to float away. By the time we got back to the first pumpout, on our way back to "our" marina, it was as late as it would have been if we had waited there in the first place.

Our host at the marina waved us into a slip where we just fit. He manhandled a power boat out of the slip and tied it up elsewhere to make room for us. We asked him eagerly about amenities: yes, there were showers and toilets up the hill in the campground, no problem. Food? Yes, we could eat in the pizzeria. They had ice cream too. Coffee in the morning? He himself would open the pizzeria and make me a pot at 7:00AM! Heaven! But unfortunately when we got to the pizzeria, we learned that the cook had called to say she would be late. No problem. Showers first. But when Judy and I found our way over rickety, splintered docks with missing boards to the building where the showers were supposed to be, we found ONE facility, offensively labeled "girls", and one coin-operated shower. Nothing seemed to have been cleaned in years and there was no toilet paper and only one toilet. We took turns in the luke-warm trickle of water. When Ken arrived he couldn't find a men's shower at all. He fetched the proprietor, who stared foolishly at the nailed-shut door and said Ken would have to use the women's shower. He also asked us what kind of pizza we wanted. Vegetable, we said, remembering the sign in the pizzeria. Sorry. Nobody had ordered ingredients, and we could have cheese and sauce, and that was it. Ken used the shower and then we all trooped down to the pizzeria. Sorry. The chef was not coming it at all it seemed. No, there were no grocery stores or restaurants in walking distance. We had toasted cheese sandwiches and instant soup on the boat. Then we went back to the pizzeria patio to wait for our friend who was bringing our van and trailer. She arrived shortly. The proprietor was nearby and I asked him if we could at least have ice cream. He fetched us four bars and gave me mine for free.

Our friend had made a mistake. We had intended to drive her to Syracuse airport that evening so she could get a shuttle back to Ithaca-but the last shuttle had left already. After some debate, we decided she and Judy would take a motel room (at the same marina where we hadn't pumped out) and we would drop her in Syracuse in the morning.

In the morning I waited till 7:15 and made instant coffee. After berry pancakes (our friend had brought berries) we derigged spinnaker lines, lifelines, the jackline and shroud tighteners. The proprietor turned up at eight o'clock carrying a pot of the most gawdawful coffee I have ever tasted. We turned the boat around in the slip so Ken could stand on a barge nearby to remove the instruments from the mast head. It was necessary to lower the mast on the water because there were powerlines over the ramp. We got the boat on the trailer and out of the water, and Ken approached the proprietor to pay up. He charged us double . . . because we took up two spaces!! We were very glad to leave North Sandy Pond Marina behind.

We dropped our friend at the Syracuse airport and pointed our van east on the New York throughway. In Rome, we got stuck in rock-concert traffic for an hour and a half in the 90 degree heat. At one rest area, a couple asked, "How many boats are you towing? Is it one, or three?" We were glad to explain. And of course it is true we were towing three boats: a canal boat, a fast sailboat, and a home for three.